Singapore – Ways to achieve net zero by 2050

Singapore will not be bound by its geographical constraints – a regional power grid, new low-carbon hydrogen, non-intermittent solar energy supply, and a holistic blended finance system will carry it to its net-zero target in 2050. Acting for many of the world’s largest energy and resources companies, Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP offers insights into the intersection between inventive policies, regulations and project financing strategies needed to attain Singapore’s goal. ByShemane ChanandLoh Yong Hui, both partners in the construction and projects, energy and resources team atRajah & Tann Singapore LLP

On October 25 2022, Singapore announced its national climate target of achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, following its commitment to reducing emissions to 60 MTCO2e by 2030. Being a signatory to the Paris Agreement, this net-zero goal is a testament to Singapore’s dedication to limit global temperature rise to below 2°C and transition to a more sustainable future.

Still, this was an ambitious promise – as a small island nation with no hinterland and limited natural resources, 95% of Singapore’s energy is generated from imported fossil fuels and Singapore faces significant spatial constraints for renewable energy production.

As such, Singapore takes an innovative and multifaceted approach in its strategies to achieve this goal, focusing on developing a diversified supply mix of energy in 2050 – encapsulated as the “Energy Reset” pillar of action in Singapore’s Green Plan 2030.

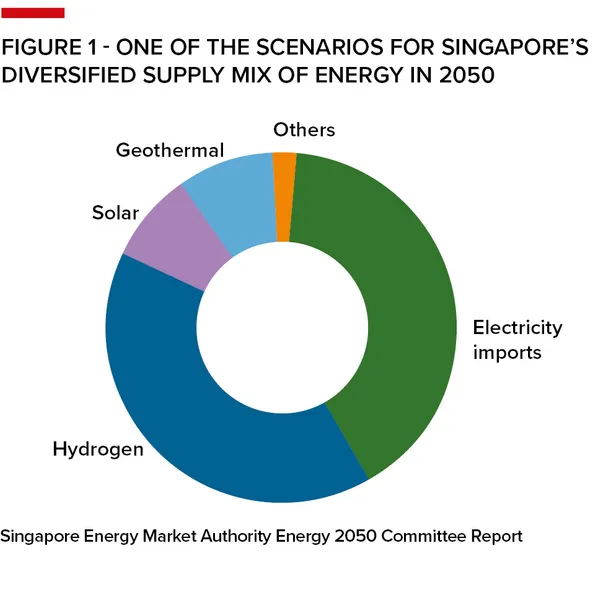

One of the possible scenarios for Singapore’s diversified supply mix of energy in 2050 is electricity imports and low-carbon hydrogen each fulfilling 40% share of the power generations needs; geothermal and solar adding up to about 20% of the supply and Others including waste-to-energy and biomethane making up the balance.

This article highlights the financing challenges Singapore faces or will face in its implementation of strategies to achieve a diversified supply mix of energy, and the regulatory collaborations between the public and private sectors that will be much needed to provide solutions and achieve Singapore’s net-zero goal.

Regional power grid

* Import targets – Singapore’s most ambitious decarbonisation initiative is the cross-border import of low-carbon electricity into Singapore. In September 2024, Singapore sets an electricity import target of 6GW of low-carbon electricity by 2035, which will account for 30% of Singapore energy needs then.

This was raised from the previously determined 4GW target, and is aimed to be achieved via a regional power grid in an extension of the landmark Laos-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore power integration project, which brought Singapore its first imports of clean energy ever, 100MW of hydropower, in June 2022.

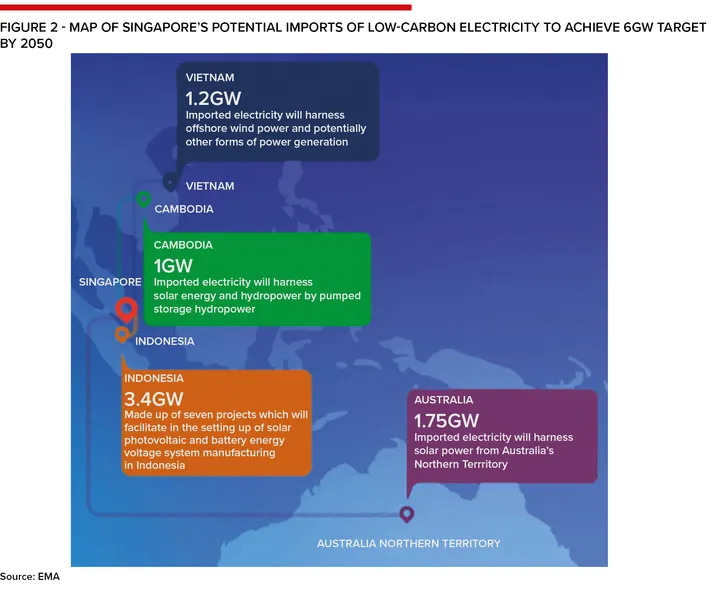

To date, Singapore’s Energy Market Authority (EMA) has issued Conditional Approvals for 10 electricity import projects from Indonesia, Cambodia, Vietnam and Australia facilitated by subsea transmission cables. This imported electricity will collectively tap on a diverse mix of renewable energy such as solar, wind and hydro power.

Of note, the EMA has awarded conditional licences for five of these projects helmed by different Indonesian companies (including Adaro Solar), which aim to achieve commercial operations from 2028. Most recently, the EMA has also awarded a conditional approval to Sun Cable for the import of 1.75GW of solar power (representing 9% of Singapore’s total electricity needs) from Australia, via formidable 4,300km long subsea transmission cables.

* Challenges – Though an exciting cross-border endeavour, the main obstacles in accomplishing this massive interconnection task are its demanding financial costs, infrastructural implications and lack of standardised regulatory frameworks contributing to high investor risk.

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, approximately S$380bn (US$290bn) is needed for the ASEAN region to boost renewable energy capacity to achieve the ASEAN target of having 23% of its energy produced from renewable sources by 2025. To upgrade domestic electricity grids (a necessary process to increase import capacity and bolster regional electricity trade), costs are estimated to be S$27bn (US$21bn).

Moreover, a policy report on the LTMS project by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute highlighted this high upfront cost is exacerbated by a lack of consensus among stakeholders on the transboundary costs of transmitting electricity from one grid to another (also known as wheeling charges), which leads to protracted negotiations for the financing of new infrastructure and effectively discourages investments in regional grids.

From a regulatory standpoint, the establishment of a regional power grid thus necessitates the alignment of market, technical and regulatory rules to ensure commercial viability. Currently, there is no unified regional grid code for ASEAN, with each country independently developing and enforcing its rules and procedures.

This must be changed as the harmonisation of these grid codes is a critical step in mitigating the risks related to regional interconnections – eg cascading grid failures – which deter financiers from investing in regional power grid infrastructure.

Importantly for subsea cable projects, which are mostly affected by cross-border joint ventures, clear financing and risk allocation arrangements between countries are required, especially with regard to whether the cables connecting the countries are financed by one or more of the interconnected countries directly, through an international financial institution or privately financed.

A precedent can be drawn from existing subsea communications cables that are largely funded by consortiums comprising private telecoms operators, technology firms and governmental entities from either interconnected country. As Robert Beckman, director of Centre for International Law at National University of Singapore, effectively summarises: “Submarine cables are the orphans of international law,” and as such its jurisdictional complexities must be addressed in its financing structures.

* A shared plan – Indeed, this need for technical and regulatory interconnectivity between domestic grids of ASEAN countries has been identified as the critical pathway to realising the regional power grid at the recent 29th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP29) Singapore Pavilion, in the panel discussion titled “Energy Corridors: Propelling the ASEAN Power Grid” on November 15 2024.

In that panel, Melissa Moi, head of sustainable business at UOB Bank, highlighted the prime position Singapore is now in to facilitate this technical interconnectivity: as announced during Singapore International Energy Week, Singapore Power Group is now the chair of the Asian Grid Operators Networks, making Singapore well placed to “drive increased dialogue [such that] at the grid operator level we have that alignment of technical specifications”, which will lay the groundwork for the larger discussions on government-to-government long-term agreements to happen in parallel.

Importantly, Moi highlighted the current availability of funding, limited only by the absence of such interconnectivity and therefore the lack of investor confidence. Similarly, Abdan Hanif Satria, executive vice-president of corporate business development and investment at PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara Indonesia, also emphasised the need for standardised grid codes between ASEAN countries, stating that without such regulatory synchronisation “seamless energy transfer can[not] happen”.

Evidently, the key regulatory challenges faced by the ASEAN countries in building its regional power grid are well deliberated by its cross-border collaborators, signalling a hopeful future for the regional power grid.

National hydrogen strategy

Secondly, Singapore is also dedicating itself to advancing hydrogen technologies and scaling up supply chains for low-carbon hydrogen, spurring a global transition towards greener shipping.

In October 2022, then deputy prime minister and minister for finance Lawrence Wong outlined Singapore’s National Hydrogen Strategy to develop low-carbon hydrogen as a major decarbonisation pathway as part of efforts to support Singapore’s commitment to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, with hydrogen expected to supply half of Singapore’s power needs by 2050.

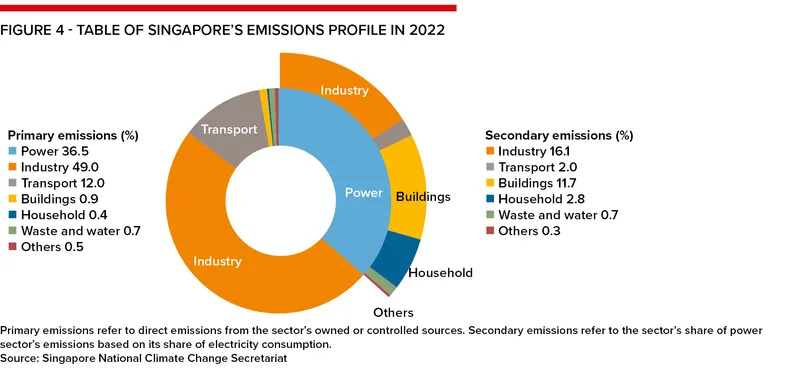

Looking at Singapore’s net emissions profile, achieving net zero would require a fundamental transformation of key sectors of the city-state’s economy such as power and industry.

In line with that, to deeply decarbonise the major hard-to-abate industries such as the maritime and petrochemicals sectors, in July 2024, the EMA and Singapore’s Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore have shortlisted two consortia (namely Keppel’s Infrastructure Division and Sembcorp-Singapore LNG) to provide a low or zero-carbon ammonia solution on Jurong Island for power generation and bunkering – ammonia serving as one of the most technologically-ready hydrogen carriers with an established international supply chain for industrial use.

However, given that low-carbon hydrogen is a nascent and developing technology hinging on present research and development efforts bearing fruit, private investors often hesitate due to the precariousness of returns.

* Government subsidies – In 2024, both Japan and South Korea sought to solve this issue by introducing a contract-for-difference support subsidy, wherein the price gap between hydrogen and existing fuels such as coal incurred by suppliers of low-carbon hydrogen will be bridged by the government to bring hydrogen capacity to market.

Since October 2024, this CfD subsidy is formally and legally in effect in Japan following the enactment of the Hydrogen Society Promotion Act. With this policy support by the government, hydrogen-related projects will become more bankable: setting firmer structures and regulations in place to ease financiers into investing in low-carbon hydrogen.

Applying this to Singapore, while the government is funding R&D of low-carbon hydrogen heavily – evident from the award of S$43m (US$32m) to six projects under the Directed Hydrogen Programme to develop Singapore’s capabilities for safe and economical use of hydrogen – the technological maturity which that may eventually bring may not be enough to boost investor’s confidence and sufficiently drive the development of a low-carbon-hydrogen supply chain.

Risk mitigation policies such as the CfD scheme should be considered and adopted, especially given its success stories in the UK’s offshore wind sector.

Solar energy

Lastly, Singapore has tapped on solar energy as a clean energy source to generate electricity since 2021, maximising spaces on rooftops, reservoirs and other offshore spaces. Currently, Singapore aims to deploy at least 2GW peak of solar energy by 2030, which will meet electricity needs of 350,000 households and eventually 10% of Singapore’s electricity demand.

Currently, a 60MW peak inland floating solar photovoltaic system sits at Tengeh Reservoir. To maintain grid reliability and resilience, Singapore has deployed Energy Storage Systems (ESS) to address solar intermittency by storing excess energy during high generation and discharging when needed.

In February 2023, Singapore launched a 285MW-hour ESS on Jurong Island – the largest in South-East Asia and the fastest globally of its size to be deployed. We were involved in both of these critical projects.

Similar to the above, investors could be deterred by ESS’s high initial capital costs and regulatory uncertainty. Under the SolarNova Programme, government bodies such as the Economic Development Board and Housing Development Board lead the deployment of solar PV systems by promoting and aggregating demand for solar PV across government agencies to drive economies of scale.

However, prior to reaching that point, blended financing mechanisms can ultimately reduce first-loss-risk exposure for private investors, thereby attracting private commercial capital and accelerating growth of Singapore’s solar power sector.

Blended finance

Blended finance – combining capital from governments, philanthropists and private-sector organisations – is becoming a key frontier in the funding of energy transition projects in Asia.

The memorandum of understanding on the ASEAN Power Grid commits member countries to conduct studies on the financing of the construction, operation and maintenance of the regional power grid, recognising that “pooling of resources by the governments and/or private sector for joint projects subject to commercial viability” may be necessary.

Taking a step further, blended finance includes catalytic capital from philanthropists, which derisks projects and improves their financial viability, thus “catalysing” further support from other funders.

Catalytic capital is concessional – it is provided in the form of equity, loans, guarantees, grants and insurances on terms more favourable than those in the market such as lower interest rates or longer repayment periods.

As such, philanthropists assume disproportionately higher risks and kick off projects using this initial investment as the foundation; thereafter which private investors are more convinced to follow suit and supply critical resources while the public sector offers further resources or technical support.

* FAST-P – At COP28, the Monetary Authority of Singapore launched the Financing Asia’s Transition Partnership (FAST-P), an international blended finance initiative aiming to innovatively channel capital from sovereign governments, development finance institutions, multilateral development banks and philanthropic foundations to investments in Asian projects that address the most urgent climate issues of today, such as energy transition.

FAST-P represents Singapore’s pioneering of a collective Asian collaborative towards decarbonisation, which Ravi Menon, Singapore’s ambassador for climate action, emphasised in his opening speech at the COP29 Singapore Pavilion last month: as Singapore accounts for only 0.1% of global emissions while Asia accounts for 50%, “the most substantive way in which we aim to do our part is to work with partners to facilitate Asia’s decarbonisation”.

* Blended finance operating platform – Significantly however, Singapore is also looking beyond the current blended finance model. In September 2024, Gillian Tan, chief sustainability officer of MAS, emphasised at the Allied Climate Partners Breakfast Roundtable the importance of advancing further and building operating platforms for blended finance instead of executing it at a mere transactional level.

Such platforms, she expounds, will facilitate capital aggregation and blending at the platform level so as to fully stretch the initial catalytic capital; be designed with “maximum additionality and minimal concessionality” to enhance the platform’s replicability; and build “scale, a diversity of use cases and the aggregation of risk and returns”, effectively setting off a multiplier effect that simultaneously facilitates the development of sustainability projects and business models.

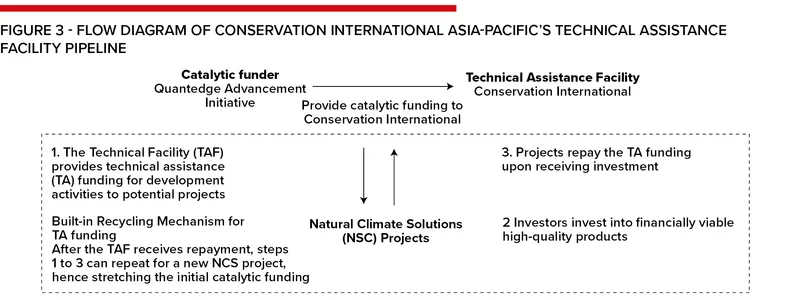

This operating platform is currently demonstrated by the Conservation International Asia-Pacific’s Natural Climate Solutions Technical Assistance Facility (TA Facility) funded by family offices, whereby the TAF provides vital capital and technical assistance (Technical Assistance Funding) to early-stage projects in order to de-risk and produce a pipeline of natural climate solutions:

Effectively, this creates a Built-In Recycling Mechanism for Technical Assistance Funding: after the TA Facility receives repayment by a project, this cycle above can be repeated for a new NCS project, thus maximising every philanthropic dollar in the initial catalytic capital.

Such Technical Assistance Funding also addresses the pipeline issue of having stagnant invest-ready capital with no viable projects to finance due to poor early-stage structuring and technological know-how.

Conclusion

Looking ahead, the next step for Singapore in its achievement of the net-zero emissions target is the financing of its imported low-carbon electricity.

Improvements in Singapore’s FAST-P initiative and blended financing structures are thus key, with tighter collaborations of trust between the public, private and philanthropic sectors.

Overall, Singapore must advance Singapore’s clean energy transition by using innovative financing strategies and developing regional regulations in tandem, in order to anticipate inevitable new challenges that come with building a regional power grid and groundbreaking clean hydrogen technologies.

* A special thanks to Yinn Teh for her valuable contribution to this article.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email leonie.welss@lseg.com