The future of financing of data centres

Financing the growth in data centre demand has never been more critical. While traditionally an area for project finance investment, we believe that other deep pockets of finance need to be explored if we are to fully meet this growing demand. ByChristian Lambie, partner,David Shearer, partner, andMirella Hart, senior knowledge lawyer, atNorton Rose Fulbright LLP

Once upon a time, not that very long ago, using the internet was a bit like going to the dentist – something you needed to do from time to time but rarely looked forward to. The dulcet tones of the dial-up modem were frequently the prelude to hours of frustration; using the internet was intentional, purposeful – often stressful – and a lot less common. We used it to search for information on Ask Jeeves – remember a world before Google? – or to order books on Amazon, back when it was only an online bookstore.

But now the internet is intertwined with aspects of our daily life in ways we may not even be aware of or, if we are aware of, we rarely pause to consider. There is a decent chance that your fridge or washing machine can be connected to the internet and, if your car is less than five years old, that it is too. Sitting in our homes or offices, it may be easy to ignore the question of where the machines that handle and process that data are housed, but property developers certainly aren’t. And neither are investors.

The demand for data centres is set to increase by more than10% year-on-year, for at least the next five years. Or, to put that in absolute terms, worldwide data traffic is expected to reach 181 zettabytes by 2025.1 One zettabyte is equal to one billion terabytes. Data centres are the backbone of the digital economy, housing data storage and processing facilities that are essential to cloud computing and – perhaps most significant in terms of reasons for growth – the development of artificial intelligence as a daily tool accessible to everyone with an internet connection. Yet, as the demand for data centres continues to grow, how can this be effectively financed?

Financing the build

While data centres are more sophisticated than simple office buildings or shopping centres, for now at least they require the construction of a building. This may, of course, not always be the case. The results of the ASCEND – Advanced Space Cloud for European Net-zero emission and Data sovereignty – feasibility study announced in June this year confirmed the feasibility of developing, deploying and operating data centres in orbit.

In the meantime, back on Earth, locating and financing the construction of these buildings is the first real hurdle in satisfying the demand for growth. A rough estimate – excluding land purchase costs, utility works, site works and professional services – for construction of a data centre in London is US$11.20 per watt.2 Clearly, location matters, which also drives land purchase costs. While it may be possible to finance the construction entirely from equity, this would depress the returns on investment for data centre developers and operators.

Project finance, at its core, does what it says on the tin and is perfectly designed to help fund the construction of data centres. And the good news is that data centres are no longer a new asset class for lenders or investors in the project finance or infrastructure space. Over the years, they have sharpened their understanding of the asset class and of the risks involved.

This increased understanding can be seen in developers being slightly less risk-averse. Given the constraints with regards to land, water and energy, they are purchasing land without the certainty upfront of whether the required permits can be obtained. Given the UK government’s recent designation of data centres as "Critical National Infrastructure", it is perhaps not a huge leap of faith to now assume that permits to build new data centres will be more forthcoming.

The structures and features of these deals also demonstrate the increased understanding of this asset class. Developers often anticipate growth and therefore request (uncommitted) accordion features, also known as incremental facilities. These avoid the need to amend the legal documentation if debt capacity is increased for additional projects or expansion of existing projects. Portfolio financing – as opposed to the financing of a standalone project – can also offer certain advantages, including:

* Cost efficiency by reducing advisory fees;

* Reducing concentration risk for financiers, through cross-collateralisation, which can also unlock the financing of smaller or riskier projects;

* Where there is a mix of brownfield and greenfield projects, leveraging the contracted assets to ensure debt capacity for new projects.

Although data centres can be financed on a wide variety of bases, we have predominantly seen project finance as the preferred structure for standalone projects. This means that the financing is provided to a special purpose vehicle, which will own the data centre, on a limited recourse basis. Lenders are willing to provide financing based on the expected revenues generated by one or more long-term offtake contracts.

However, portfolio financings – such as NAV or borrowing base facilities – can differ substantially from standalone project financings in a number of ways. For example, financial covenants are usually tested at a portfolio level rather than per individual project. Draw-stop and event of default mechanics may not be triggered merely by an individual project being in default, depending on the importance of the project within the portfolio.

That is not to ignore some of the potential downsides to portfolio financing. It would increase a lender’s exposure to a single sponsor (or sponsors) consortium and, in the context of large demand for financing, might cause lenders to run up against exposure limits. Concentration risk runs the other way too. From a sponsor’s perspective, a portfolio approach may insulate smaller projects from draw-stops and events of default due to their size being sufficiently immaterial in the context of a wider portfolio.

However, if one of the larger projects in the portfolio were to hit, say, a draw-stop, then that would likely act as a draw-stop across the entire portfolio, rather than being limited to a single project. Both sponsors and lenders will need to carefully evaluate the relative risks and rewards of taking a portfolio approach, particularly whether forgoing the ring fencing that single project financings may benefit from is outweighed by the benefit of being able to spread the risk of breaches on a single project across a wider portfolio.

Project finance has a significant and probably primary role to play in financing data centres, and it likely to retain that primacy for a long time. Nobody is suggesting otherwise and this is a tried-and-tested path to raising debt. But, as history has repeatedly demonstrated, a monocultural ecosystem is neither healthy nor resilient. And we need the capital and expertise that project financiers possess to be recycled into the construction of new data centres, not to spend years tied up in increasingly mature infrastructure. It is time to look at embedding securitisation into the data centre financing eco-system.

The emergence of securitisation

To understand the role that securitisation can play in financing data centres, it is helpful to cast our eyes to how the market has developed in the US.

Securitisation involves packaging cashflows into securities and selling them to investors. While both securitisation and project finance utilise ring-fenced SPV structures, the investor base in a securitisation can be far wider and often results in lower-cost capital.

Over the last five years, asset-backed securitisation (ABS) of data centres has started to come into its own. In the US, US$1.125bn of securitised notes were issued in the first 144A ABS in 2018, followed by the inaugural commercial mortgage-backed securitisation (CMBS) deal in 2021 of US$3.2bn. As at the start of October, this year, data centre issuance had reached US$32bn, of which 74% was in the ABS market and 26% in the CMBS market.3

Europe by contrast has been slower out of the starting blocks when it comes to data centre ABS. Vantage Data Centres, the first to issue in the US in 2018, also broke ground earlier this year, marking the first data centre ABS issue in Europe. Smaller in size, at £600m, it also included an additional £100m in unfunded variable-funding notes. This transaction also marked the tenth securitisation for Vantage, since 2018, and its ninth green debt issuance. More on ESG later.

While any financing technique can, potentially, be used to meet any financial need, certain techniques suit particular needs better than others. Project finance works very well for the construction and development of infrastructure assets. Project financiers are well versed in assessing the risks and rewards involved in taking visions on the drawing board to physical reality on the ground. While securitisation can do this – and, indeed, has – it is not securitisation’s forte. The jigsaw piece where securitisation fits best is in providing financing for mature cashflow-producing assets.

Securitisation and project finance should in many respects complement each other perfectly. Project finance funds the building of the assets and getting them up to stabilised, cashflow-positive status. Securitisation can then refinance the project financing and enable the sponsor to leverage the cashflow generated by the data centre. Such refinancing should drive the following virtuous circle for all involved

* The project financiers can increase the velocity of their capital and ultimately increase their total returns4;

* Securitisation investors can benefit from stable medium-to long-term returns, allowing them to provide finance at a lower cost (relative to project finance offered at the development stage) to sponsors;

* Lower cost long-term finance will increase the profitability of the sponsors’ investments; and

* This in turn should give sponsors the opportunity and incentive to re-invest profits into new projects.

The basic structure of a securitisation

We have said it before but it merits repeating here – there is no securitisation market. Securitisation is, rather, a financing found in a variety of market sectors. Securitisation is – in its origins, at least – the act of taking an asset that is not readily or easily tradable as a security, such as a trade or lease receivable or mortgage loan, and converting it into a security that is tradable and liquidity can improve pricing for a borrower.

Why does this observation matter? Primarily, because without that understanding it would be easy to assume that there is a one-size-fits-all when it comes to securitisation of data centres.

There are many different forms of securitisation techniques that can be utilised in the financing of data centres. For example, UK whole business securitisation, popular for more than a decade in the leveraged acquisition market, found a home in the financing of large operating businesses with, most often, a significant real estate component. This is useful if you want a real estate mortgage to give substance to your security over operational cashflows. UK whole business securitisation left its mark on some significant UK infrastructure and, as ever, it is prudent to keep an eye on history when carving a new way forward.

This is not to say that data centres ought simply to replicate the UK whole business securitisation model. They need to forge their own path and, for example, the recent release of proposals for rating criteria by Moody’s and by S&P earlier this year are a step in the right direction.

Asset types, the tenant mix, the nature of the real estate, the different types of leases found in the data centre market sub-sectors, termination rights, expected renewals, void or semi-void periods, operator strength and history, and more, are all explored in the rating agency proposals. What will be relevant to you will depend very much on the deal you want to sell, and – more importantly – the intended investor base.

Without an investor there is no securitisation. Knowing what you are trying to sell, and to whom, should be the starting point. The lawyers and arrangers can then work out the best legal and cashflow structure to achieve this. Rating agency criteria, whether used to rate a public or a private deal, can help shape this debate.

The environment

When discussing data centres, the environmental debate is never far from the agenda. Concerns about environmental impact have already led to restrictions being established in places such as Ireland, Singapore and Amsterdam. The US has also enacted a New Energy Act, imposing energy efficiency requirements on data centres.

These environmental concerns are only going to grow with the increased use of AI. AI hardware typically consumes more power than a standard data centre. It also generates more heat, requiring in turn greater cooling. The cooling also needs to be powered. Governments are already concerned, and rightly so, about the potential impact of data centres on diverting power from other uses and/or requiring yet more carbon intensive power production. This problem isn’t going away and if we are to solve the financing of data centres we need to do that within an ESG framework.

Vantage is a good example of how securitisation can be used to sustainably finance data centre growth. Recent figures also suggest that 77% of enterprises would be willing to pay a premium for a more sustainable data centre solution.6 If businesses are willing to pay more to house and process their data sustainably, this ultimately feeds through the entire value chain, right down to the investors.

This is where securitisation arguably has the potential to lead the way forward, compared with project finance. While local regulations and legislation may impose environmental targets and restrictions that apply no matter which form of financing is used, the added layer of achieving "green bond" status, or complying with other sustainability-linked requirements from investors, may lead to a greater ESG commitment.

A holistic way forward

Project finance on its own may well be able to provide the debt finance required to build the data centre capacity that the world needs. But it doesn’t need to carry all the load and exploring different financing techniques will ultimately be to the benefit of project financiers and developers.

Footnotes

1 - Source: Statista

2 - Source: Turner & Townsend Data centre cost index 2024

3 - Source: Bank of America, using JLL data

4 - This does, of course, assume that there is a ready supply of new projects to which project financiers can lend – with regard to data centres, this seems likely to be the case for the foreseeable future

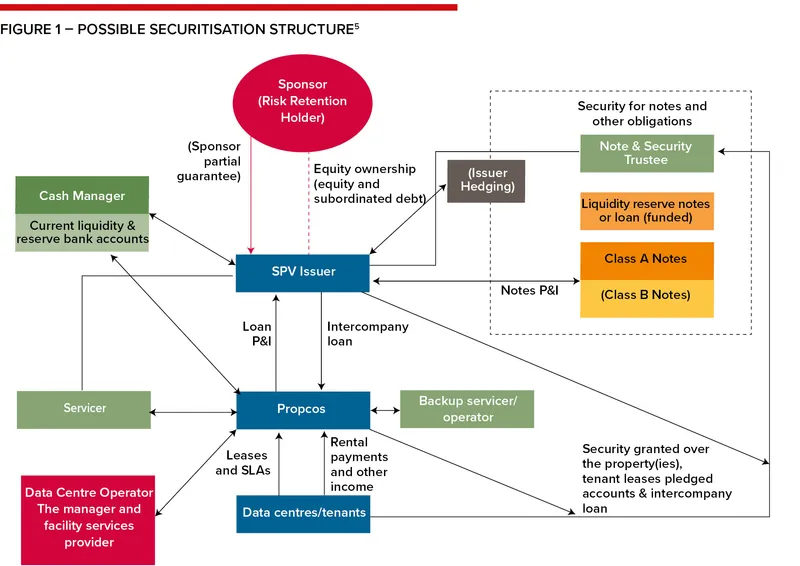

5 - While not wishing to undermine the argument that there is no single "market" for securitisation, it is nevertheless helpful to have an idea of what a structure could look like

6 - 451 Research’s Voice of the Enterprise Report: Datacenters, Sustainability 2023. Part of S&P Global Market Intelligence

To see the digital version of this report, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email leonie.welss@lseg.com