Transforming South Africa's energy landscape

It is hard to believe that it’s been more than a decade since the world turned its eyes to South Africa as the host of the 2010 FIFA Men’s World Cup, a momentous event that showcased the nation's vivacity and potential on the global stage. Around the same time, South Africa's electricity sector stood at a crossroads, fighting with a number of challenges ranging from aging infrastructure to an insatiable demand for power. ByInes Pinot de Villechenon, director,Green Giraffe Advisory.

Although football and renewable energy do not, at first glance, have a lot in common, that particular point in time was interesting. In 2010, the country's energy landscape was in the early stages of transformation from a heavily polluting electricity sector, with the seeds of a renewable energy revolution just beginning to take root. Initiatives such as the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP) were about to be launched, signalling a shift towards a more diversified and sustainable energy mix. While being a "green" World Cup was perhaps not the overriding criterion in 2010, South Africa ran a successful tournament back then, it could reasonably be questioned whether it could do the same today given the ongoing effects of load shedding.

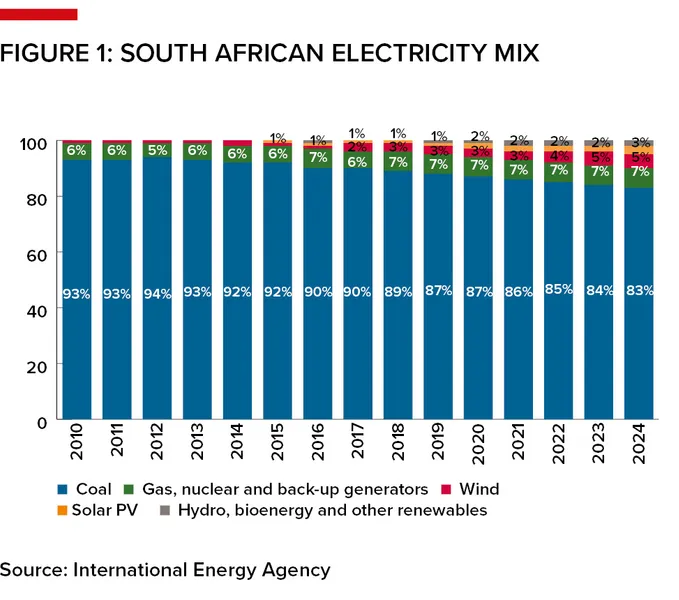

Since 2010, South Africa's electricity sector has begun a journey of very significant changes, characterised by efforts to diversify its energy mix, promote sustainability, and improve access to affordable and reliable electricity. Although coal is still by far the main source of electricity generated in the country, it has been steadily diminishing, starting to give way to a more balanced and environmentally conscious mix that includes renewable energy sources and not least because of the first REIPPPP rounds.

Central to the continuation of this change will be the further liberalisation of the electricity market, a process aimed at fostering competition, innovation, and efficiency, not to mention relieving some of the operational and financial burden on Eskom, the state-owned utility. Eskom is today (and has been historically) vertically integrated but is undergoing a process to split it into generation and trading entities which will also enable this liberalisation. Further regulatory reforms, private stakeholders’ engagement and technological advancements will then act as additional catalysts.

Transition from public to private procurement

It’s worth looking at the history of the electricity market in the South African context to understand the scale of the changes we are talking about. Until recently, the South African electricity supply industry operated under a single buyer model, where Eskom was acting as sole offtaker for all the electricity produced in the country and as the sole producer for electricity on the grid, too.

The first phase of changes saw the introduction of independent power producers (IPPs) to the South African electricity market as an initiative from the government to diversify the energy mix and attract private investment. On the renewable energy side, IPPs were initially required to participate in competitive public tenders to secure power purchase agreements (PPAs) with Eskom for their projects. The REIPPPP bid windows (BW) 1 to 5 organised between 2011 and 2021 marked considerable success stories, facilitating the development of several gigawatts of renewable energy capacity across the country, proving the case for a world beyond reliance on fossil fuels and stimulating investment in the sector.

BW6 in 2022, exclusively awarded solar projects and underscored the importance of geographical symmetry between projects and grid capacity available. In the gas sector, the introduction of IPPs further bolstered South Africa's energy resilience and contributed to the transition towards cleaner energy sources, compared with coal electricity generation. The result of this can be seen in Figure 1, with an energy landscape becoming gradually more diversified and renewable energy sources now contributing more than Eskom’s nuclear generation.

In addition to bringing much needed generating capacity onto the grid – that it is clean is a clear benefit, but the capacity is needed, full stop – REIPPPP has offered a pathway to project financing utility-scale renewable energy projects, through its robust framework, reliable offtake agreements, and strong guarantees. The importance of now having a funding community that understands renewable energy projects is a further achievement. Although REIPPPP, for which BW7 is ongoing, as a framework relies heavily on public sector involvement and support, when compared with the "old" way of procuring electricity generation, ie Eskom builds, it has been remarkably efficient and disciplined as well. Take Eskom’s new coal-fired plants Medupi and Kusile: both have faced extensive delays and cost overruns over more than 15 years – during the same time multiple GW of renewable energy generation has been added to the grid in a cost-effective manner.

As South Africa continues the first part of its marathon journey towards a more diversified and competitive landscape, admittedly with a few water breaks along the road, the argument for maintaining the previous model solely focused on REIPPPP tenders has grown weaker. Although there are some differing and at times competing political objectives, what we have witnessed in recent years is recognition at large on the part of each of the government and Eskom of the reality that further changes and progress need to be facilitated.

The impact of Eskom’s financial situation on the state’s balance sheet adds weight to the imperative to look for alternative options for renewable energy procurement. Indeed, without this important additional factor, one could have argued that continuing on with REIPPPP rounds at speed would be enough in the short term. However, REIPPPP is not neutral for the government balance sheet and coupled with an increasing demand for security of supply from the private sector (a more prevalent first driver for corporate power procurement in South Africa than the green objectives we might see in other markets, although these are important too in South Africa), facilitating purely private solutions alongside successful public-private partnerships recently became an important objective.

Consequently, the government and Eskom have undertaken some courageous steps to restructure and clarify the processes for electricity generators and offtakers, thus engaging a smoother transition to a liberalised electricity market. Key milestones in this journey include:

* The pivotal 2022 policy amendment that removed the 100MW generation licence threshold for IPPs, requiring only NERSA registration instead. This change has been instrumental in unlocking private PPAs and propelling South Africa's energy transition and deployment of renewable energy projects

* Further reforms, such as the amendment of the Electricity Regulation Act, have laid the foundation for the transformation of South Africa's electricity market with; i) the establishment of a national regulatory framework for the electricity supply industry under NERSA’s guardianship; ii) the unbundling of Eskom and the formation of the National Transmission Company of South Africa (NTCSA); and iii) the creation of a competitive multi-market structure for the electricity sector

* Additionally, the recent publication of the revised Grid Connection Capacity Assessment (GCCA) and the creation of the Energy One Stop Shop have enhanced transparency in grid capacity and streamlined permitting and licensing processes

These developments have opened avenues for increased private generation and facilitated wheeling (use of the national grid by private power producers, where the end buyer is not Eskom but another private party), enabling large-scale PPA activities and the transportation of privately generated power across the national grid. Wheeling has therefore emerged as a scalable solution to accelerate further adoption of renewable energy together with the liberalisation of the electricity market.

Nuances and complexities

South Africa is now embarking on an ambitious programme aimed at evolving the electricity market to a stage where electricity can be freely bought and sold in different ways: (i) with regulated PPAs between the renewable energy project and the transmission service operator NTCSA, (ii) with private PPAs between licensed generators and final offtakers; and (iii) via trading platforms, enabling market participants to engage in hourly and daily trades.

In the long-term vision of a fully liberalised electricity market, there hence emerges a promising landscape of flexibility and security for all stakeholders. Such a market structure inherently provides additional comfort by simplifying the process of sourcing new offtake agreements should a private PPA be terminated. This flexibility not only enhances the resilience of the electricity supply chain but also opens the door for innovative market entrants to challenge the status quo.

The potential for fully liberalised trading platforms is huge, as these platforms can enable real-time, dynamic trading activities, making the market more competitive and efficient. As South Africa progresses towards a largely decentralised market, the role of energy traders will become increasingly important. They serve as the crucial link between electricity generators and consumers, ensuring an efficient and dynamic energy trading ecosystem. The cumulative effect of these changes promises not only to transform the energy landscape but also to empower consumers and encourage a more rapid transition to renewable energy sources.

However, in the interim period before the full realisation of a liberalised market, the financing landscape faces immediate challenges and uncertainties as it needs to continue its evolution from one based on the public-private partnership approach of the REIPPPP and one where public sector involvement is limited to enabling regulations.

Despite the clear economic benefits of renewable energy supply, which continue to attract corporate offtakers to commit to relatively long-term agreements, the possibility to enter into creditworthy PPAs extending beyond 15 years is becoming increasingly difficult. This has important implications for project financing, particularly given the capital-intensive nature of renewable energy projects in their initial stages. To compensate for the shorter duration of PPAs, before there is a track record of free trading of electricity on the market, a higher tariff may be necessary to amortise the initial investment adequately, potentially affecting the attractiveness of projects to investors and offtakers.

Moreover, where there is an arrangement with a trader available, the risk of engaging with traders without a robust balance sheet or an established operational track record creates further complications. Such entities might not be in a position to offer back-to-back contracts with potential final offtakers, introducing an additional layer of risk.

Financing trends

The challenges presented above highlight the need for a more nuanced approach to project financing and risk assessment in the evolving landscape of renewable energy procurement and distribution, as the sector navigates the transition towards a more open and competitive market. First, it is imperative to adopt a balanced approach that aligns short to medium-term needs with long-term strategic objectives from the outset. One possibility could be to proactively consider options for refinancing down the line, thereby providing flexibility and sustainability to projects over their lifecycle. Of course, entering into robust and well-structured PPAs is crucial too, with a focus on securing commitments from off-takers with strong financial backing and a proven track record. However, all stakeholders, lenders included, will need to form a view on the ongoing demand for electricity and the ongoing competitiveness of a project – the analysis of breakeven pricing and the levellised cost of energy of a project becoming increasingly important.

Partnering with established traders, such as Etana, Empower Trading, PowerX or other reputable entities, can give additional comfort to the lenders on the project’s ability to manage competitive and strong offtake. Furthermore, we have seen some actors deciding to establish proprietary trading platforms, such as Envusa Energy, a jointly owned renewable energy venture between Anglo American and EDF Renewables South Africa, or Lyra, a partnership between Scatec, Standard Bank and Stanlib, thus enabling the IPP to exercise greater control over the entire value chain, minimising counterparty risk and building a take-or-pay arrangement at portfolio level. Finally, we expect there will be further opportunities to capitalise on cross-border trading in due course.

Despite some of these challenges for bankability of private-to-private projects in the short to medium term, we find local lenders are adopting a pragmatic approach and displaying flexibility to make those deals happen. The substantial pipeline of projects and quite simply the demand for electricity will eventually raise questions about liquidity, highlighting the potential role of other players such as local debt funds and international commercial banks.

As such, the sooner the market can develop a track record and give further certainty to the lending community on the regulatory framework, the better. Overall, the evolving financing trends underscore the importance of collaboration, innovation, and diversification in driving sustainable renewable energy development in South Africa.

The trajectory of South Africa's renewable energy sector reflects challenges on the path towards a more liberalised energy landscape. Although liberalisation has happened in many other markets globally, it is rare for such a radical reform to be accompanied by whole-scale changes in the energy mix. So, to some extent South Africa is breaking new ground in many different ways.

While private offtake agreements have gained traction, there remains a need for public procurement programmes to support the development of large-scale projects if the country is to meet its targets (and needs). There is a recognition of the critical social development role of electricity, necessitating a balance between private sector participation and government oversight.

It remains to be seen whether the South African regulatory framework could change further in the future. A deregulated South African electricity market is all very new, and the liberalisation of the country’s electricity sector is still in its early stages. Eskom unbundling is just starting but we already trust that the emergence of the national transmission company will play a crucial role in the strengthening and the financing of the grid.

Nevertheless, what is happening in South Africa is very encouraging and the opportunities for clean energy deployment are immense, offering environmental benefits, economic opportunities, and social empowerment. The remarkable progress achieved in renewable energy deployment to date signals a promising future for the sector – who knows, perhaps a future FIFA World Cup in South Africa could be powered exclusively by renewable energy? As Green Giraffe Advisory, we are excited about the upcoming opportunities and committed to supporting stakeholders in navigating this evolving market landscape. If you identify challenges or opportunities, we stand ready to provide our expertise and support.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com in Asia Pacific & Middle East and leonie.welss@lseg.com for Europe & Americas.