Evolution of the renewable energy offtake

At NORD/LB’s Energy Transition Seminar, we discussed the latest trends in renewable energy project finance, with a deep dive on the evolution of renewable energy offtake. Throughout this evolution, sponsors and banks have continuously adapted and innovated to craft optimal debt offtake structures to satisfy investor return hurdles and get projects off the ground. ByNiels Jakeman, head of energy origination, structured finance Europe,Nord/LB.

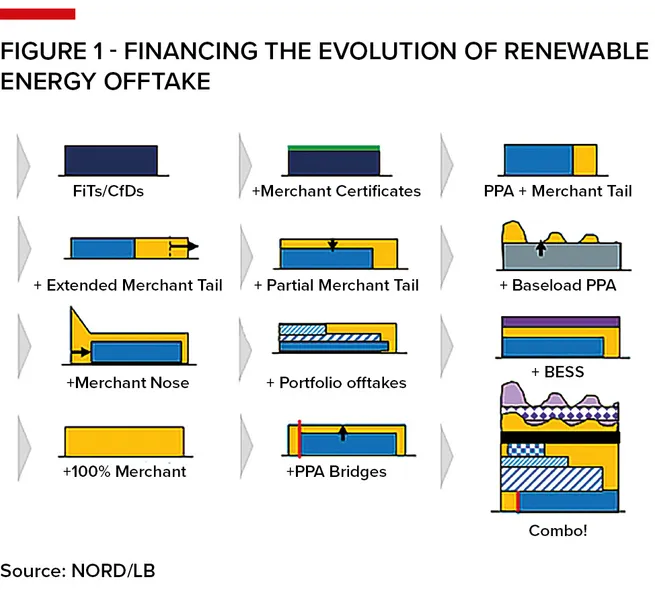

Over the course of almost a decade, offtake structures have been transformed from subsidised fixed feed-in-tariffs (FiTs) to unsubsidised diversified portfolios, actively managed using a suite of offtake products with flexible debt products to match. This is the story of this evolution from a project financier’s perspective, and where we might be headed.

The evolution

The good old days. The story begins over a decade ago with solar and wind projects benefiting from 20-year FiTs/contracts for difference (CfDs), which shielded projects from price risk, credit risk, and in many cases volume and grid risks. Financiers’ primary focus was on: i) ensuring regulatory certainty of a given subsidy scheme; ii) the expected technological performance; and iii) assessing resource uncertainty. Little did we know of the innovation that lay ahead!

In certain markets, the first introduction to merchant risks for renewable projects came in the form of renewable "merchant certificates", which were traded according to supply-demand dynamics, such as renewable obligation certificates (ROCs) in the UK, Sweden’s electricity certificate (Elcert) scheme and large-scale generation certificates (LGCs) in Australia.

With many certificate schemes lacking a fixed floor price, these were nerve-wracking times for lenders, who lay awake at night at the thought of prices plummeting to zero due to potential market oversupply! Bankers dipped their toes into merchant financings, initially adopting highly conservative views with cover ratios, such that in their nightmare scenario contracted cashflows would remain just sufficient to cover debt service.

Utilities, energy retailers and intensive consumers were obligated to purchase the renewable certificates, and entered into long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) with projects to secure attractive prices and manage their own price exposures. The renewable energy power purchase agreement (PPA) market was born, initially with tenors of circa 15 years, until the end of a given certificate obligation period.

Banks would size debt on only these contracted cashflows, but it wasn’t long before PPA tenors started to shorten and project leverage ratios would deteriorate to uneconomic levels. With asset lives at >20 years the only option was to take a view on post-PPA wholesale prices to reach a minimum gearing levels – and so the "PPA + merchant tail" was introduced. Weary of this long-term price exposure, lenders sought to mitigate tail risks with strong re-contracting obligations and cash sweep structures, keeping the exposure to post-PPA revenues to a bare minimum.

But as demand for long-term PPAs from projects outweighed supply, market competition continued to drive prices to lower levels – at times even below the levellised cost of energy (LCOE) of projects. Sponsors, in particular those relying on project finance debt, had little choice but to enter into relatively uneconomic contracts just to secure their financing.

Relief came in the form increasing asset lives backed by longer warranties from original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) extending to 25 years, allowing sponsors and banks to take a longer-term view on payback periods via "extended merchant tails." With the longer debt tenors, post-PPA balloons continued to increase and banks focused on creating strong incentives for projects to recontract, such as mini-perms and cash reserves, rather than imposing firm obligations.

The scarcity of long-term PPAs also meant that lenders would seek to eke out as much leverage as possible against them by tightening cover ratios, leaving limited buffers to absorb unforeseen risks such as grid costs, transmission losses or curtailment.

In the hunt for some cashflow buffers and improved equity returns, sponsors began exploring "partial merchant" strategies in which a proportion of a project’s volume would be left uncontracted, resulting in higher expected near-term revenues. Once again, banks had to adapt, and over time were able to take increasing amounts of near-term merchant price exposure for debt sizing purposes, mitigated with more conservative cover ratios and breakeven prices in combination with other structural mitigants.

A competitor to the standard PPAs came with the introduction of insurance-backed financial hedges, not in Figure 1, providing protection against price volatility, in some cases with the added bonus of compensating for wind output or solar irradiance, eg proxy revenue swaps. The downside of these instruments was the little if any connection to the technical performance of the underlying project, which introduced new risks around unavailability and in particular force majeure events such as extreme weather – which were famously stressed in Texas during the winter of 2020/21.

Innovation to generate additional contracted revenues continued with the arrival of "baseload PPAs", which required projects to sell a fixed volume on an hourly basis over the PPA tenor in return for a decent increase in contract prices. Although the higher contracted prices were welcomed, they introduced projects to capture price exposure – projects having to fulfil their contracted volumes even during periods of low output, which typically coincided with higher priced periods.

Extensive scenario analysis eventually got sponsors and lenders comfortable that baseload PPAs could be mitigated with sufficient shaping cost buffers and liquidity reserves. Needless to say, the extreme market conditions of 2022–23 tested the boundaries of these scenarios and some tough lessons were learnt, particularly in the Nordics and for projects that were unable to actively manage their prices exposures.

As wholesale prices in Europe reached at all-time-highs, sponsors sought to offset higher interest rates, up 3 percentage points since 2021, and supply chain costs with a new structure – the "merchant nose" – pushing forward the start date of PPAs to allow sponsors to benefit from higher near-term prices, while providing buffers against potential construction delays. And for lenders, the key question became how much additional debt we could balance on this "nose", while mitigating the risk of prices dropping faster than expected.

There were also strategies involving multiple different offtake contracts for a given project, ie "portfolio offtakes", seeking to strike a balance of long-term PPAs to secure attractive debt terms with a proportion of higher priced alternatives offtakes, such as:

* Shorter-term PPAs – Typically better priced due to higher near-term price expectations and a more favourable supply-demand balance – according to Pexapark, five year PPAs price on average €18/MWh1 higher than 10-year PPAs across Europe,

* Sub-investment grade offtakers – With credit enhancements in the form of letters of credit/parent company guarantees would typically be needed to ensure banks don’t discount them as merchant.

With the rapid cost declines of Li-Ion batteries, storage projects have quickly become the new asset class se

eking to strike this debt-offtake balance. The impressive build-out in the US has so far been largely supported with long term capacity-based contracts. Europe has trailed behind due to a combination of clear market signals, regulatory hurdles and the availability of long term offtake agreements, however a number of projects have been able to secure financing based on merchant structures and revenue floor contracts.

The real opportunity lies in hybrid projects – renewables + "battery energy storage systems (BESS)" – now the norm in markets such as the US, offering; i) invaluable negative correlations with long-term merchant prices; ii) the opportunity to provide more attractive generation profiles to offtakers, with many now seeking to secure their demand on a 24/7 basis; and, in turn, iii) superior debt terms compared with standalone solar, wind or BESS projects. As capture prices continue to come under pressure across several markets in Europe, it won’t be long before this becomes standard practice on this side of the pond.

Why sign up to a contract at all? Over the last few years there have been multiple projects financed on a "100% merchant" basis; however, in general these have been limited as financiers remain concerned with holding large amounts of long-term merchant risk. It’s also becoming increasingly common for banks to have merchant limits, which would constrain banks' overall exposure to merchant wholesale prices – 100% merchant projects would quickly utilise those limits!

There has, however, been an increasing desire for "PPA bridges", giving sponsors the valuable flexibility to defer entering into PPAs during construction or soon after commercial operation date (COD), with the expectation of being able to secure more favourable terms.

The combo!

This brings us to the final part of the chart in the evolution … labelled "the combo!" – pulling together colourful features from each of the above structures, and likely to represent the future model in renewable energy offtake:

1 – Recognising the value of a diversified portfolio of assets in generating more stable output and cashflows, especially if portfolio construction has considered zero or negative correlations across technologies, locations and capture prices;

2 – Securing sufficient long-term CfDs and/or PPAs to ensure long-term price stability for banks and managing their overall merchant limits;

3 – Complementing with a suite of alternative offtake products, including higher priced short-term PPAs, some sub-investment grade offtakes as well as a manageable proportion of baseload PPAs; and

4 – Actively managed on a portfolio basis to enhance cashflow stability, minimise route to market costs, and allow for offtake agreements to be entered into at their most optimal time.

Looking ahead

Reflecting on the past decade, the speed of offtake evolution has been remarkable. It has by no means been an easy ride, as sponsors and banks have had to navigate highly volatile markets, extreme weather events, supply chain disruptions and rising interest rates. Yet despite these headwinds, renewable energy capacity has continued to grow year-on-year, with thanks to the sheer determination and structural innovation of many to find ways of optimising their debt-offtake structures to satisfy investor return hurdles.

Government-backed CfDs will continue to play a critical role in delivering our decarbonisation targets in Europe; however the future of renewable energy offtake will need to draw on lessons from the last decade to enhance project revenues and avoid pitfalls. And lenders will need to continue to evolve, seeking to provide tangible financial value against the benefits of the colourful combo, which someone said is just missing some “palm trees”.

Footnote

1 - go.pexapark.com/l/891233/2023-12-22/h52jn/891233/1703230881Nz4J4nYC/Getting_ready_for_2024.pdf

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com in Asia Pacific & Middle East and leonie.welss@lseg.com for Europe & Americas.