Tax credits – Transferability and structures

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 seeks, among other things, to achieve decarbonisation goals on a national scale, largely through federal income tax credits. ByHayden Baker,Jeffrey Davis,NadavKlugman,Elena Millerman, andMostafa Al Khonaizi,White & Case.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA): i) extended the production tax credit (PTC) and the investment tax credit (ITC) for electricity generated from wind, solar and certain other renewable resources; ii) expanded the resources eligible for the PTC and ITC, including by allowing the ITC for energy storage technologies such as batteries; iii) extended and expanded the tax credits for carbon capture, utilisation and sequestration; iv) introduced new technology-neutral PTCs and ITCs for electricity generated with zero emissions to replace the current parameters of the PTC and ITC when they expire; v) added new tax credits for the production of hydrogen and certain energy equipment manufacturing and; vi) added new tax credits for electricity generation at qualifying nuclear facilities that were in operation prior to the enactment of the IRA.

In addition to the goal of decarbonisation, the IRA aims to achieve other policy goals by changing the structure of the PTC and ITC to allow the full credit amount only if certain prevailing wage and apprenticeship (PWA) requirements are met and by adding bonus credits for projects located in energy communities, located in certain low-income communities or constructed with a certain amount of domestic content. The IRA also introduced the opportunity to transfer certain federal income tax credits to third parties, referred to herein as transferability, which creates a new avenue to monetise those tax credits as an alternative or enhancement to traditional tax equity structures.

Following the release of proposed regulations by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) in June 2023, transferability of tax credits has become a viable option, with many market participants modifying existing structures and creating new structures to provide alternatives in using or selling the tax credits generated by a project. The project finance industry is adapting rapidly and creatively to embrace the new structures to allow transferability, bringing in new investors and lowering the costs of capital for clean energy projects.

The IRA allows a sponsor to sell tax credits directly to a third party. However, the so-called direct transfer has some shortcomings, from the perspective of the project owner: (i) it will not capture the full value of the tax credits because they are sold at a discount; (ii) it does not generate a step up in tax basis, so, absent further structuring, the credits in the case of an ITC deal and depreciation are based on the project’s cost instead of its fair market value; and (iii) it does not facilitate the monetisation of depreciation.

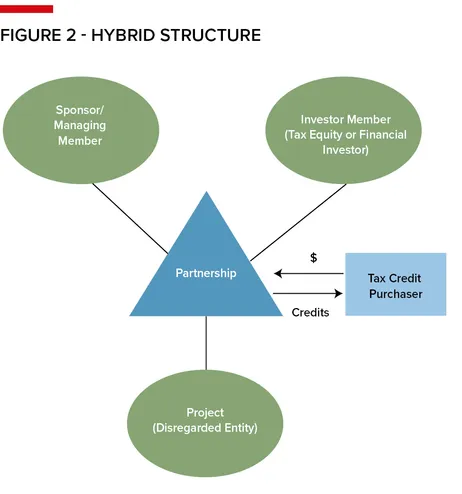

As a result, we have seen the emergence of a hybrid structure that combines the traditional partnership flip with a transfer that addresses these shortcomings and significantly increases value to all stakeholders. It also allows existing tax equity investors to expand the market through syndication and facilitate entry of tax credit buyers who can rely on due diligence and structuring previously conducted by the tax equity investors.

In this article, we will explore the hybrid structure and other emerging structures. Some aspects of these structures are becoming standardised, but there are still many deal terms that are not. Transferability and other features as discussed below create a playing field for all incumbent and new stakeholders to grow the market efficiently and effectively.

Structures

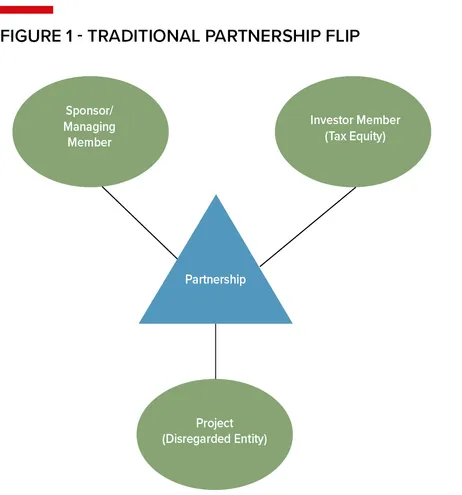

* Traditional partnership flip – The most common vehicle for monetising tax credits has been the traditional partnership flip structure. In the typical transaction, the tax equity investor initially is allocated 99% of the tax benefits and a lower share of the cash. When the tax equity investor achieves an agreed after-tax internal rate of return, the allocation of tax benefits flips down to 5%; hence, the name partnership flip. The tax equity investor’s return is derived from a combination of the tax credits, the tax benefit of accelerated depreciation and cash distributions from the project. The sponsor has an option to purchase the tax equity investor’s interest after the flip. This structure is time-tested and benefits from a safe harbour from the IRS. The tax equity investor must have enough “skin in the game” to constitute an equity investor entitled to receive the tax credits, but they have less project risk than a typical joint venture partner.

* Hybrid structure – The emerging hybrid vehicle uses the traditional partnership flip structure, but the tax equity investor (or in some cases, the sponsor) can cause the partnership to sell to a third party the tax credits that otherwise would be allocated to the tax equity investor or sponsor. Because the partnership will make the transfer of the tax credits, this is sometimes referred to as a t-flip. The transfer is effected pursuant to a tax credit transfer agreement or a tax credit purchase agreement (TCTA).

This structure appeals to an investor that may not have the tax appetite for the full amount of the tax credits or depreciation – and in some cases an investor that has limited or no appetite for the tax credits or depreciation – may not be able to predict its tax appetite in the future or may want the ability to spread its capital across other projects. By having the transfer-out option, the hybrid vehicle provides flexibility to the tax equity investor. In some cases, the tax equity investor will require stringent conditions around its obligation to fund, including, for example, with respect to certainty about the buyer’s ability to buy the tax credits.

The tax credit buyer will be able to purchase the credits at a discount and thereby reduce its tax liability, while receiving a nice return on its investment. The tax credit buyer also can benefit from the due diligence and underwriting already conducted by the tax equity investor. The deal terms are relatively straightforward: the buyer is buying or committing to buy a tax credit at an agreed price based on the assurances, indemnities and guarantees provided by the sponsor, together with tax credit insurance. PTC deals are generally simpler; ITC deals are subject to recapture and other project risk that can make them good candidates for insurance.

From the developer’s perspective, the hybrid vehicle provides a relatively predictable structure and deal terms, while allowing flexibility for the tax equity investor to use the tax credits, sell the tax credits or a combination of the two.

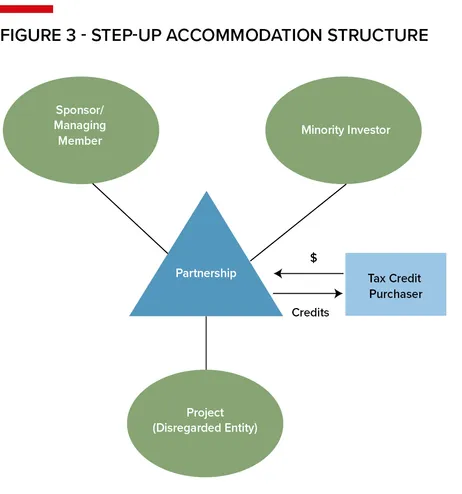

* Step-up accommodation structure – A variation on the direct transfer structure introduces a fund investor or other minority investor to facilitate a basis step-up and to monetise depreciation but not give any value to the tax credits. Instead, the responsibility for finding a buyer for the credits remains with the developer. The minority investor may be entitled to a preferred return, although a version of this structure provides the sponsor with a preferred return. The depreciation may be allocated pro rata between the sponsor and the minority investor.

However, the depreciation may be allocated disproportionately to the sponsor, either because the minority investor may be a fund that has limited or no tax appetite or the sponsor may want a shield against taxes on any gain triggered from a sale of the project to the partnership entity. To support the step-up and help ensure that such sale is respected, the purchase price should reflect fair market value and be supported by an appraisal. Some sponsors rely on an internal partnership structure without a third-party investor designed to achieve a similar step-up.

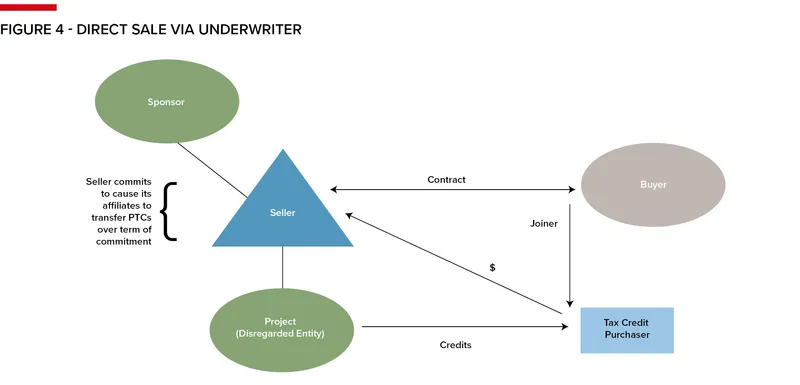

* Direct sale via underwriter – Another variation of the direct transfer structure involves the execution of a TCTA with a single party that essentially acts as an underwriter with the right to assign its rights and obligations under the TCTA to one or more assignees. Those assignees will then purchase the tax credits directly. For practical reasons, there may be limitations on the number of assignees and the credit rating of assignees. This allows the sponsor to have a commitment for the tax credit sale in advance of identifying the ultimate buyers and provides the sponsor with a more streamlined transaction, initially with a single counterparty.

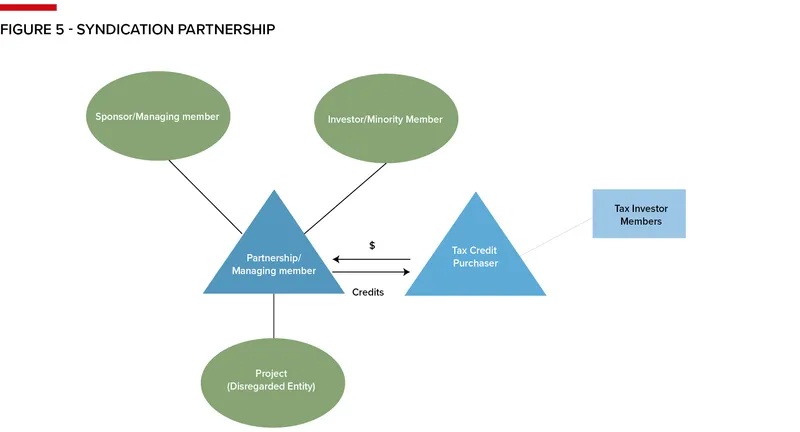

* Syndication partnership – Another structure involves a direct transfer of tax credits to a partnership that would enable partners to invest for different periods (essentially entering and exiting the partnership) to match the timing and value of the tax credits purchased by the partnership with their needs. Although this could be used for both ITCs and PTCs, it is likely better suited for PTCs as they are generated over time based on actual production output.

Optimising for debt

All of the above explanations and illustrations are simplified and omit any debt financing. Practically, debt financing can be used to augment and complicate each of the structures described above. Development, construction and working capital loans, as well as term financing, are available, and markets continue to develop to better accommodate or leverage the transferability function.

Debt options are available at different levels in the structure and can be used depending on the type of project, the tax credits sought – ITC vs PTC – and overall project development and financing strategy – eg, project vs portfolio; recourse vs non-recourse financing; projects that benefit from tax credit insurance discussed below – vs those that do not.

Project financing in the renewable and clean energy space can generally be structured in three different ways: i) back-leverage debt on the sponsor’s interest in the tax equity partnership; ii) project level term debt, usually only if there is no third-party investor; or iii) holding company-level debt covering the sponsor’s interest in the portfolio(s) owned.

One option worth considering for certain lenders is to divide their lending interest and investment interest in the project by being the back-leverage lender to the project and concurrently the tax equity or minority investor in the partnership, enabling the step-up in basis. Because this structure involves parallel equity and debt investments, it requires coordination between the terms and cashflows of both investment vehicles and, for certain types of financial institutions, may require careful structuring for regulatory purposes.

Tax credit insurance

The business of insuring tax credit risks is rapidly expanding in scope and becoming more streamlined. Established precedents and a record of claim-handling allows insurers to pool similar risks effectively while maintaining costs. The insurance market has adapted to underwrite the following categories of tax risk: project sale, partnership structure and allocations risk; tax credit qualification risks (including tax basis, PWA, domestic content, energy community and placed in service); basis risk; recapture risk with respect to ITCs; tax credit transfer risks (including production, PWA compliance and tax audits); and change in tax law and other laws.

As tax credit structures become more standardised and as the outcomes of the various tax credit risks become better known and quantifiable, the more stakeholders can appropriately allocate risks among themselves by working with the limits, deductibles and exclusions of the tax credit insurance market. As we have seen in other transactional risk insurance markets, tax credit insurers continue to adapt to the practical needs of the renewable and clean energy market, including the types of risks covered and their diligence requirements for underwriting. They can optimise diligence on a case-by-case basis depending on the availability of diligence by a third-party investor and their familiarity with the tax credit structure and risk allocation selected.

Conclusion

Clean energy investment has long been constrained by the scarcity of tax equity investors re

lative to the addressable market. The flexibility afforded by transferability is easing this constraint in two ways. First, transferability enables the direct transfer of tax credits through a simple TCTA, allowing sponsors to sidestep the complex tax equity investment structures and sell credits directly. Since the complexity of tax equity investment structures has long been a barrier to entry for investors, these direct transfers are particularly compelling for those projects that typically have difficulty accessing tax equity, whether as a result of their risk profile, sponsor experience, size or otherwise. Second, through the structures we outlined above, the transfers of credits out of (or into) partnerships are enabling, in effect, the syndication of tax credits – thereby unlocking previously untapped tax credit investor appetite.

The opportunity presented by transferability is to establish robust, repeatable structures that can efficiently allocate investor capital, accelerate the development of clean energy projects and ultimately help decarbonise the economy. Across all aspects of the clean energy sector, the most successful relationships have been built over long periods of time by repeat players who understand the value of mutually beneficial relationships.

In large measure, their success has come from identifying and accommodating the needs, objectives and limitations of their counterparties. As sponsors, buyers and investors navigate the structures we describe above, industry participants would be well served to do the same with an awareness that we are growing this market. In doing so, the industry will more quickly optimise these structures for efficiency, scalability and repeatability, all of which are needed to achieve the full potential of the IRA’s tax credit incentives.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com in Asia Pacific & Middle East and leonie.welss@lseg.com for Europe & Americas.