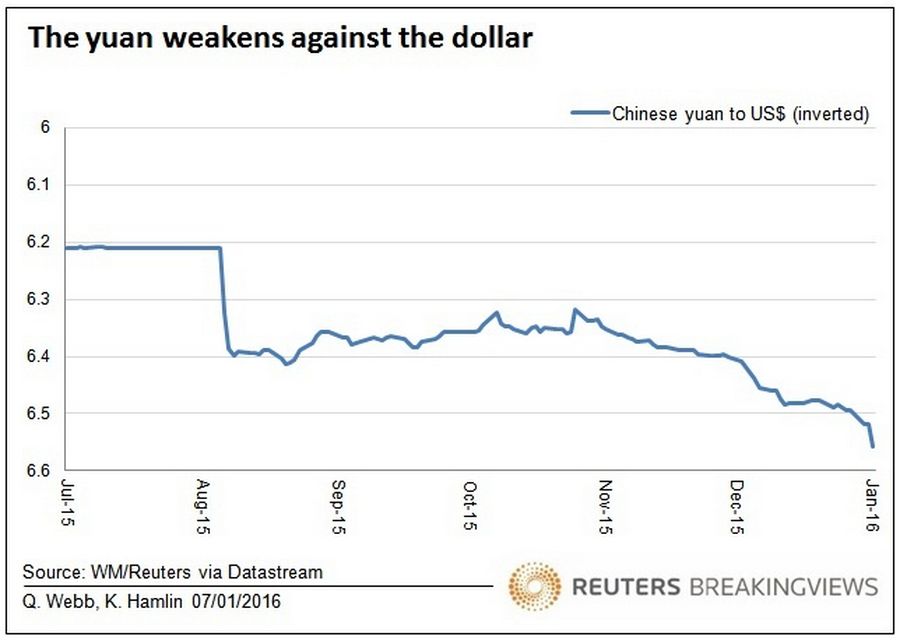

For the second time in less than six months, market turmoil in China is rattling the rest of the world. As in August last year, the trigger is a sudden slide in the value of the yuan, which in turn has dragged down domestic stocks. Though the cause of the selloff is uncertain, the implications for the rest of the world are ominous.

The Chinese currency is down 1.5 percent against the U.S. dollar in fewer than four full days. That’s only slightly less than the supposedly one-off depreciation that surprised global investors last summer. The latest slide has triggered a sell-off in Chinese stocks, twice activating new “circuit-breakers” which suspend trading when the benchmark CSI 300 index moves more than 7 percent. On the morning of Jan. 7, the market closed within half an hour of the opening bell.

Broadly, there are two theories for what is going on. The first is that the Chinese authorities have concluded a hefty devaluation is the least bad solution to the country’s economic predicament. Renewed fears of a currency war have prompted investors to flee major trading partners like Australia and South Korea, while also putting pressure on commodity prices. A barrel of Brent crude oil now sells for little more than $33.

Chinese authorities counter that the yuan is only weak when compared with the U.S. dollar. Measured against a broader basket of currencies, the renminbi was more or less flat last year. Besides, China is still running a healthy trade surplus, which lessens its incentive to seek a competitive advantage by devaluing.

Yet if China really has no grand plan, that gives weight to the second theory: that planners are losing their grip on the world’s second-largest economy. Last year’s bungled stock market intervention and mini-devaluation punctured the myth of Chinese bureaucratic infallibility. The latest ructions reinforce the belief that officials are struggling to reconcile contradictory demands: promoting market forces while preserving stability; and rebalancing the economy while continuing to meet increasingly unrealistic growth targets.

Whether China’s latest market upheaval is by design or default, it’s little surprise that investors are increasingly assuming the worst.