Central bankers make unlikely tragic heroes. Yet Mario Draghi is becoming exactly that by pushing on with a doomed fight to revive inflation.

The European Central Bank president on Dec. 3 lowered the deposit rate to minus 0.30 percent from minus 0.20 percent. He also extended the duration of the ECB’s monthly asset purchases into 2017 and said euro-denominated municipal and regional bonds would qualify for the buying programme, effectively giving himself more ways to inject new money into the European economy.

There were good grounds for such easing. Euro zone consumer prices are rising at an annual rate of only 0.1 percent and central bank staff reckon inflation won’t return to its target of just below 2 percent in the next couple of years.

Yet Draghi’s efforts are probably for naught. Disappointment that he didn’t do even more lifted the euro as much as 3 percent above the low seen in the run up to the ECB meeting – the opposite of what’s needed to help exporters or stimulate inflation by making imports more expensive. Euro zone bond yields rose and stock markets fell.

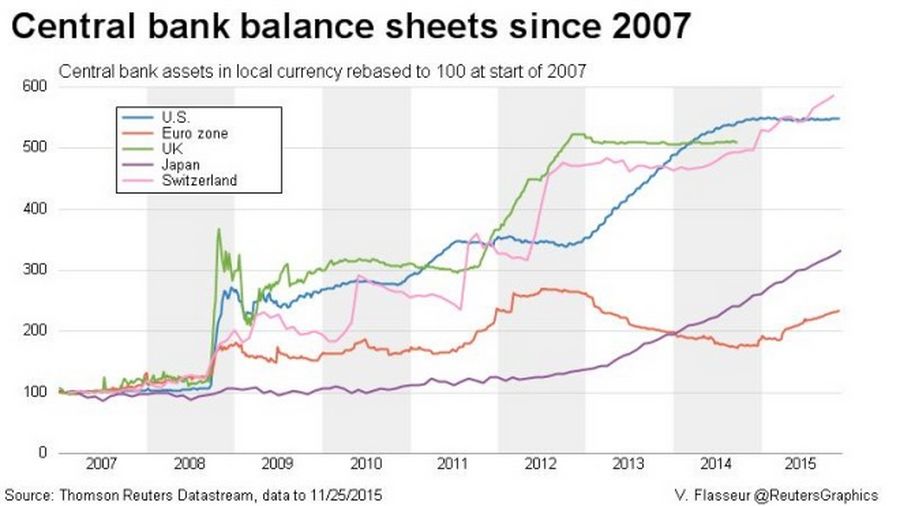

Forces beyond Draghi’s control, such as oil prices, are also working against him. The ECB has been buying bonds for nearly nine months without any noticeable impact on inflation. The U.S. Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan have experienced similar impotence.

Draghi’s problem is that while easing tends to make banks more willing to lend, a recent ECB survey showed that small euro zone companies already feel they have access to more credit than they need for the first time since 2009. They are more concerned with finding customers of their own.

Draghi knows this and yet keeps coming up with new ways to ease policy because he has an inflation mandate to meet. Right now, that looks to be beyond his powers. Like tragic heroes, he may be remembered for trying to fight destiny rather than for succeeding.