The newly global yuan could get weaker. The International Monetary Fund has endorsed China’s financial reforms by adding the renminbi to its basket of reserve currencies. The largely symbolic boost will do little to counteract the pressure from a slowing economy, lower interest rates and capital outflows.

The long campaign to add its currency to the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights has forced the People’s Republic into some uncomfortable contortions. On the one hand, officials have loosened some controls on capital flows and allowed the yuan’s value to fluctuate more widely in an effort to satisfy demands that a reserve currency be “freely usable”. Yet after a botched mini-devaluation in August spooked global investors, Chinese leaders have also insisted that the yuan will remain broadly stable.

The central bank has reconciled these objectives by propping up the currency in both onshore and offshore markets. Though the intervention has restored calm, it is not sustainable, even with foreign currency reserves of $3.5 trillion.

Over time, China’s new status may encourage central banks and other investors to hold more assets in renminbi. But that process – if it happens at all – is likely to be slow. Beijing’s bureaucrats still monitor cross-border capital flows, and have recently clamped down on unauthorised transfers. The freely traded Japanese yen has been an official reserve currency for decades, yet accounts for less than 4 percent of central bank reserves.

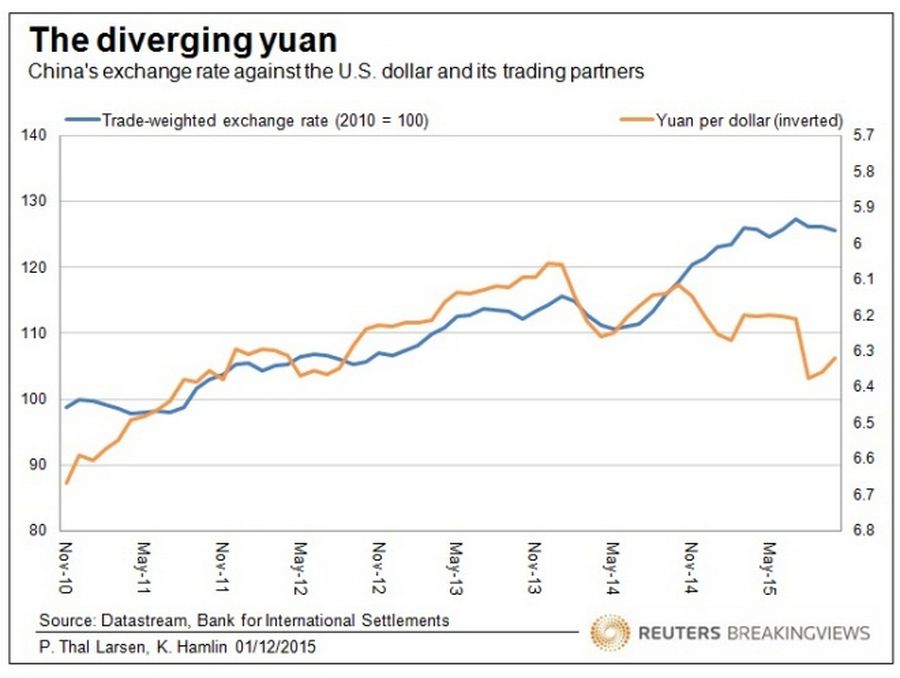

In the meantime, there are good reasons for the yuan to slide. China’s economy is slowing; the PBOC has cut the cost of borrowing six times in a little more than twelve months. Moreover, the Chinese currency only looks weak when compared with the resurgent U.S. dollar. Measured against China’s main trading partners, the yuan is up about 2 percent this year, according to an index compiled by the Bank for International Settlements.

In the past month, the official exchange rate has declined 1.3 percent against the U.S. dollar. Its offshore counterpart in Hong Kong has fallen more. Despite the prestige of an IMF endorsement, the currency could drop further.

This view has been altered to correct the foreign currency reserves figure in the third paragraph to $3.5 trillion from $2.5 trillion.