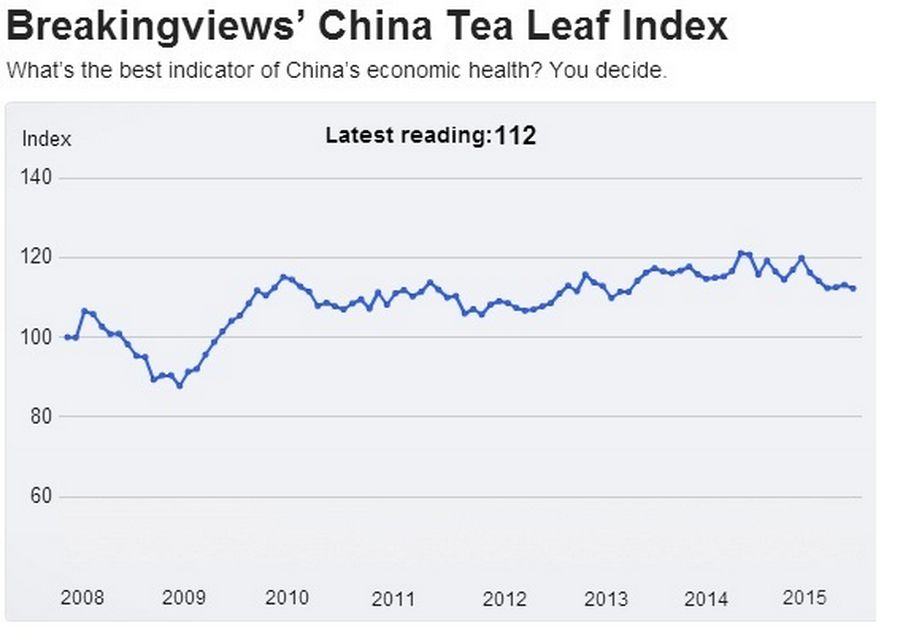

Breakingviews’ refreshed Tea Leaf Index shows China’s economy is moving at different speeds. Robust demand for technology, services and consumer goods is playing an increasingly important role in the world’s second-largest economy. Yet traditional sources of strength like heavy industry and construction remain weak.

Widespread mistrust of China’s official GDP data means investors are always looking for other measures of performance. The Tea Leaf Index offers an alternative view of China’s development, drawing from ten hand-picked metrics. The interactive graphic allows users to choose the inputs they think offer the best insight.

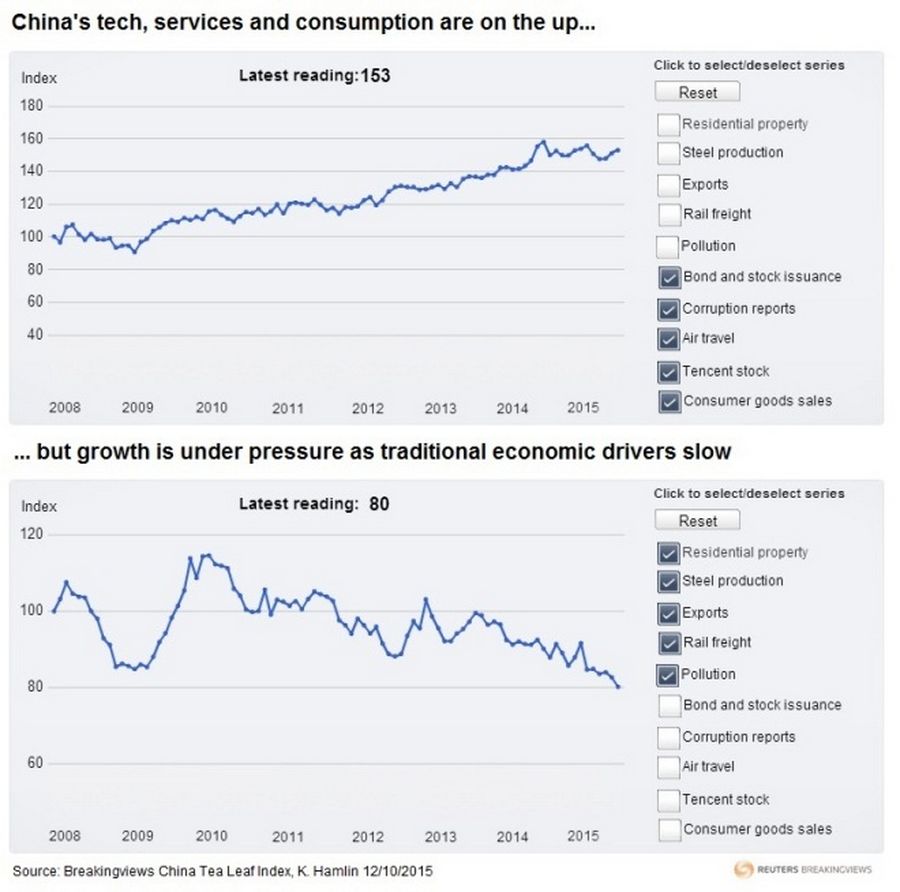

The first five inputs capture traditional sources of China’s economic growth. Exports provide a snapshot of the manufacturing sector. Steel production is a bellwether for heavy industry. Investment in new residential property is important because construction creates jobs and drives urbanization.

Rail freight volumes offer an insight into the domestic economy. Meanwhile, the level of pollution in Beijing is a gauge of activity in the industrial North East – and a reminder that rapid growth can be unhealthy.

The remaining five categories highlight newer sources of growth. Retail sales measure the confidence of Chinese consumers. Domestic air travel is a benchmark for tourism and business activity. Corporate issuance of bonds and shares show the extent to which financial markets, rather than state-owned banks, are allocating capital.

The technology sector is also important, though rapid changes make measuring this a challenge. We have chosen the share price of Tencent, whose WeChat app helps more than half a billion Chinese citizens communicate, shop, and access local services.

President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive is another important variable. Stamping out graft should make growth more efficient and equitable, though fear of punishment may discourage cadres from approving new projects. Local media mentions of “graft” and “flies and tigers” – the preferred term for corrupt officials of all sizes – show the momentum of Xi’s campaign.

Right now, the tea leaves suggest China’s traditional economic engines have stalled. Select the first five inputs and the index has fallen below the depths of the global financial crisis in 2008. On the other hand, the remaining five categories produce an index which is close to its all-time high.

The bad news is that services and consumption are not yet strong enough to compensate for weakness in more traditional activities. The ten indicators, combined, produced a reading for August of 112 – the lowest level for more than two years.

In the longer term, Beijing may be happy to sacrifice quantity of growth for quality of growth. But for now, the tea leaves produce a bitter aftertaste.