China has reimposed stability on the yuan – at a price. Almost two months after the central bank shocked global markets with a mini-devaluation of its currency, calm has returned. Yet the promise of letting market forces play a greater role in setting the exchange rate remains distant.

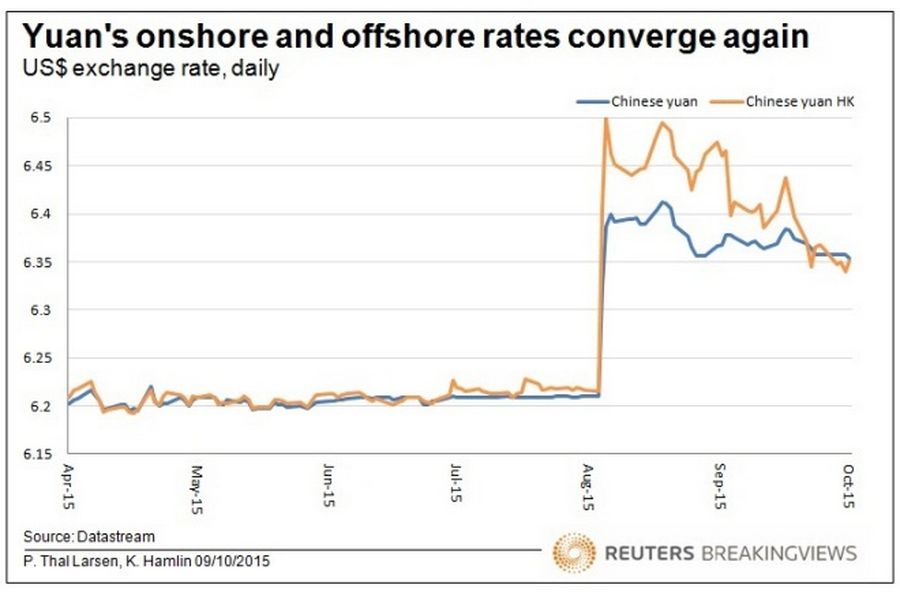

Trading in the renminbi in the last few days has made recent volatility seem like a bad dream. On the morning of Oct. 9, the Chinese currency reached its strongest level against the U.S. dollar since the People’s Bank of China shifted policy mid-August. Meanwhile the offshore yuan traded in Hong Kong – which had weakened as investors anticipated further depreciation – now trades at a slight premium to its onshore cousin.

Restoring stability has been expensive, however. The immediate cost is evident in China’s shrinking foreign exchange reserves, which fell by a record $180 billion in the third quarter. Though multiple factors affect the value of reserves, it’s fairly clear that the central bank has intervened heavily to prop up the currency, both onshore and offshore. Meanwhile, officials have been forced to tighten their enforcement of China’s capital rules in an attempt to prevent cash from leaving the country.

The longer-term question is whether the saga has undermined China’s quest to encourage international use of its currency. The evidence is mixed. In August, 2.79 percent of global payments activity was conducted in yuan, surpassing the Japanese yen for the first time, according to global transaction services organization SWIFT. Yet recent inflows in Hong Kong suggest investors are still fleeing the renminbi: the Hong Kong Monetary Authority has spent around HK$80 billion ($10.3 billion) since the beginning of September to prevent its currency from breaching its peg against the U.S. dollar.

The International Monetary Fund is due to decide next month whether to add the renminbi to the basket of currencies that make up its Special Drawing Rights. Inclusion would be a big symbolic endorsement of China’s long campaign to gain international recognition for the yuan.

But the PBOC’s recent grip on the currency suggests its plan for a more flexible exchange rate is on hold. The longer that continues the more August’s devaluation looks like a costly mistake.