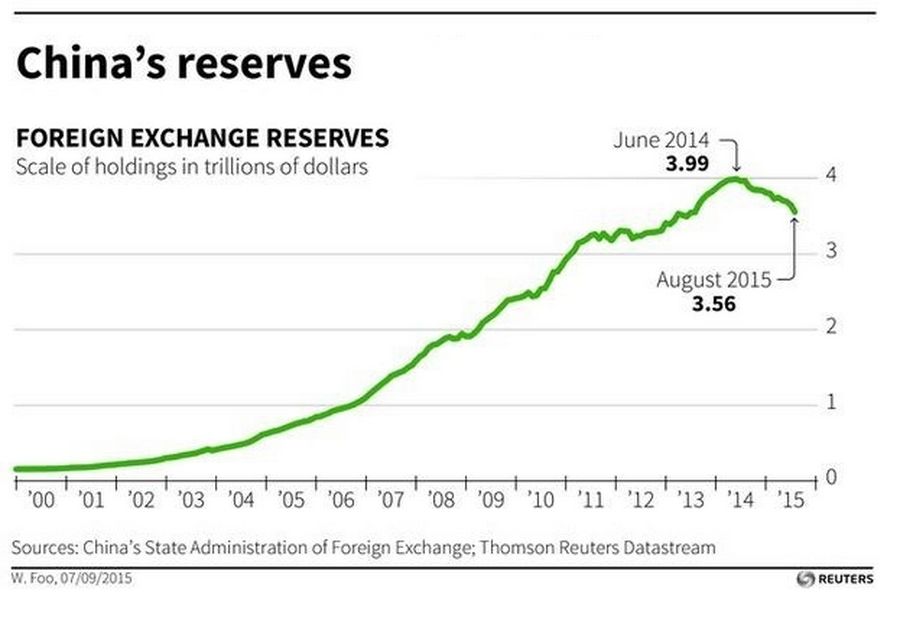

China’s giant foreign exchange hoard just got a bit smaller. A $94 billion decline in August – the biggest absolute drop on record – shrank the country’s reserves of U.S. dollars and other currencies to $3.56 trillion. The outflows have raised concerns about capital flight in the wake of China’s botched devaluation. Yet the bigger risk is of a domestic squeeze.

For the world’s second-largest economy, losing 2.6 percent of its reserves in a single month is more than a blip. Indeed, the figure would have been larger but for the euro’s recovery in August, which boosted the value of China’s holdings of the European currency in dollar terms. The best guess is that China spent well over $100 billion defending its currency in the aftermath of the “one-off” shift in the yuan’s value in mid-August.

Yet not all outflows are equally worrisome. The prospect of a weaker Chinese currency has shocked investors who spent the past five years happily assuming an ever-stronger renminbi. That is why Chinese companies are rushing to repay U.S. dollar debt, foreign multinationals are shifting cash reserves into other currencies, and overseas investors are unwinding yuan-denominated bets.

If the value of the yuan was genuinely set by market forces, the currency would probably fall. Instead, the central bank is dipping into its foreign-exchange reserves to keep the exchange rate stable. It cannot do so indefinitely, especially if rising U.S. interest rates make the dollar more attractive. Yet if China’s overseas liabilities shrink along with its assets, the process could bring some benefits.

Even so, large capital outflows come with two headaches. The first worry is that Chinese citizens try to move their money out of the country. A recent crackdown on unofficial money-changers, such as pawn shops in the gambling haven of Macau, suggests officials are nervous about capital flight.

The second problem is that, each time the People’s Bank of China sells dollars in return for yuan, China’s money supply shrinks. The central bank can offset this by allowing Chinese banks to reduce their large reserves of domestic currency. But the risk is that the PBOC struggles to keep up with capital outflows. A liquidity drought is the last thing China’s slowing economy needs.