It was a shining beacon of China’s promise to usher in a convertible currency. But now the country’s offshore yuan has become a lightning rod for capital outflows from the mainland.

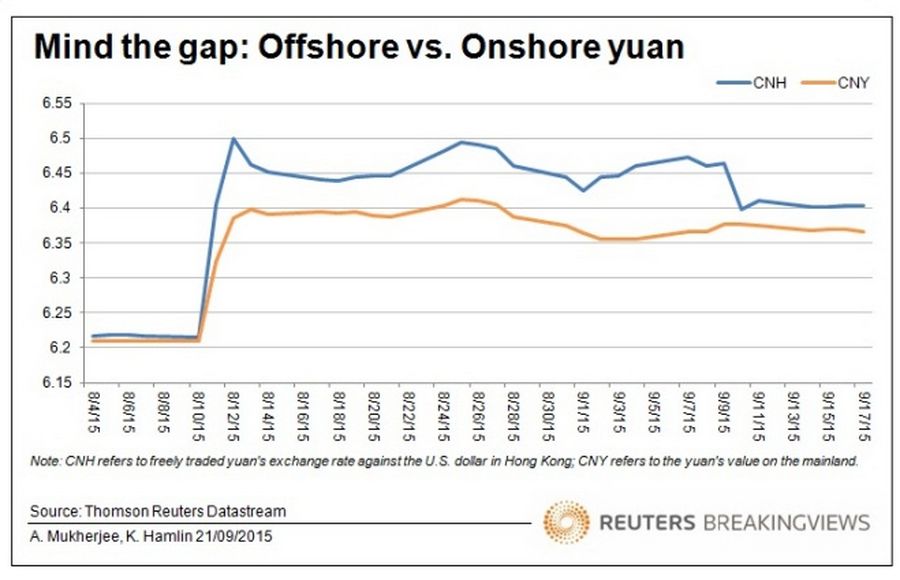

The currency, traded in Hong Kong and known as the CNH, has in recent weeks been persistently weaker than its more tightly controlled onshore cousin. It is currently 0.5 percent cheaper against the U.S. dollar than the onshore yuan, or CNY. The gap between the two has been as wide as 1.7 percent since the People’s Bank of China devalued the currency on Aug. 11.

This isn’t what China’s economic planners had in mind. They have been promoting the offshore yuan as a way of stimulating the currency’s international status, before easing capital controls at home. It has been a hit. In the Bank for International Settlements’ last survey of global currencies, daily turnover in the spot offshore market was 70 percent of the $20-billion-a-day onshore market.

This situation worked well as long as both currencies were rising in value against the U.S. dollar. Exporters’ dollars went to the mainland where they swelled the People’s Bank of China’s foreign-currency pile. Holders of offshore renminbi deposits and yuan-denominated dim sum bonds were happy owning assets in an appreciating currency.

Now the tide has turned. The offshore yuan is weaker because China’s economy is cooling while the central bank is intervening to prop up the currency. Chinese importers have a greater incentive to sell renminbi onshore. The same goes for a small group of investors who can access both markets. That’s putting pressure on the PBOC to provide dollars from its kitty, which has shrunk by 11 percent since hitting almost $4 trillion in June 2014.

The PBOC had hoped its devaluation would align the onshore exchange rate more closely with its offshore cousin. Since that backfired, the leadership is left with two bad choices. It could choke CNH liquidity to kill speculation, but only at the risk of undermining China’s ambition to join the International Monetary Fund’s elite currency club. Failling to intervene, however, puts it under pressure to devalue again.

It isn’t clear which option Beijing will choose. But as long as capital is looking to get out of China, the offshore currency that was once a poster boy for reform will remain a problem child.