China’s central bank is still on the hook, even after surprisingly strong second-quarter growth.

The mainland’s GDP expanded by a better-than-expected 7 percent, matching first quarter’s performance. The statistics bureau said growth had stabilized and was “ready to pick up.”

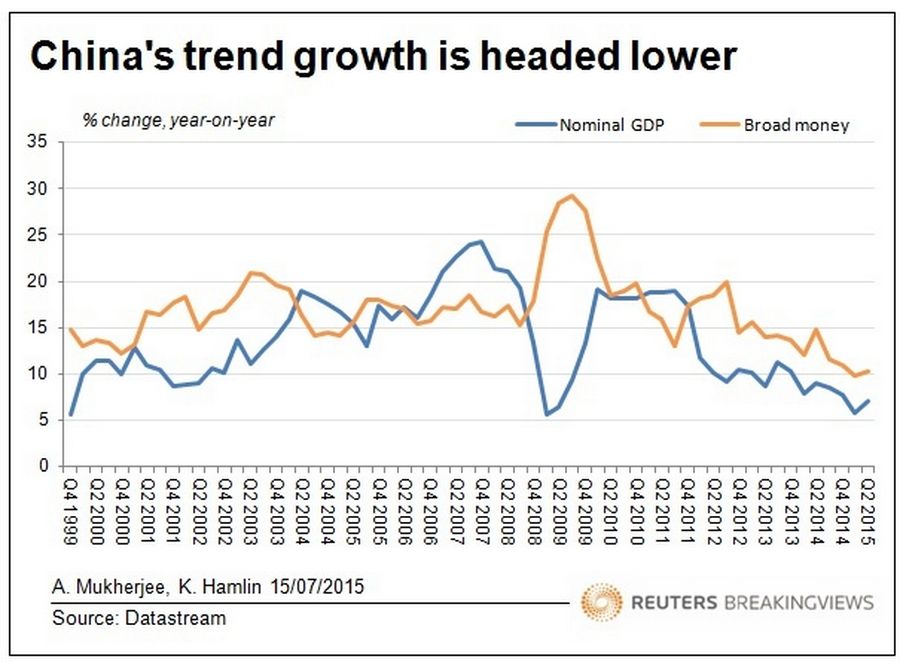

That looks overly optimistic. One red flag is property investment, which is rising at its weakest pace since 2009. Another worry is the wariness among consumers and companies: money supply in the economy is slowing despite four cuts in interest rates since November.

Disinflation is now entrenched. Strip out real GDP growth of 7 percent from nominal GDP growth of 7.1 percent, and the average price of Chinese output grew just 0.1 percent from a year earlier between April and June. That’s hardly going to prompt Chinese companies to embark on an expansion spree – not when they have truckloads of debt to repay.

The debt overhang is rightly seen as a threat to financial stability, though the recent rebound in stock markets makes a sudden collapse less likely. Even then, the People’s Bank of China may have to ease monetary policy further, if only to prevent the onset of outright deflation.

China’s working-age population has already started shrinking. Debt, deflation and a deteriorating demographic profile make for a dangerous mix. Monetary policy can’t reverse population ageing, but a bout of inflation would at least help reduce the real burden of debt. Instead, if borrowers are forced to deleverage, economic growth could slow down uncontrollably, like it did in Japan in the 1990s.

Cutting interest rates will present its own risks. A one-way bet on yuan depreciation could exacerbate capital flight. But even if the latest GDP report conveys a sense of false stability, doing nothing is not an option.