Investor redemption may be nearing for investment banks. Most lenders’ wholesale units have destroyed value for seven years. Some may have done so again in the first quarter of this year. JPMorgan kicks off results season next week and Chief Executive Jamie Dimon said in his April 8 annual letter to shareholders that returns could be attractive in the long run, if not the short term.

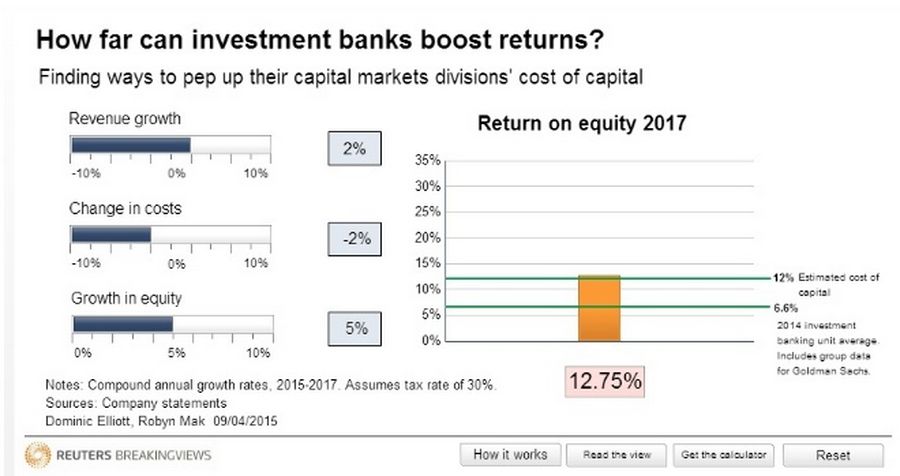

But if the biggest players cut costs by a relatively modest 2 percent per year while expanding revenue at the same rate, the industry could produce a combined return on equity of more than 12 percent by 2017, a Breakingviews calculator shows.

Of the world’s 12 largest banks, only Wells Fargo and Goldman Sachs generated returns above their cost of capital last year, according to an analysis in Financial News by Roy Smith and Brad Hintz, professors at NYU Stern School of Business.

Investment banking is the main drag on performance. The average ROE produced by Goldman Sachs and the capital markets divisions of eight big U.S. and European groups was 6.6 percent last year, according to Breakingviews calculations. That’s barely over half what McKinsey estimates is the industry’s long-term average 12 percent cost of capital.

But the picture is not as bleak as it looks. Fines and settlements pulled down the figure. Exclude these and apply a 30 percent tax rate, and the combined return was just in double digits, at 10.7 percent.

That makes the challenge of beating the cost of capital a bit less daunting. Volatile markets have boosted trading volumes in the first few months of this year. Assume this delivers a lasting boost to revenue, lifting income by a modest 2 percent a year over the next three years.

Banks still need to shrink, though. Some European groups need to cut gross assets. And regulators may introduce floors for risk weighting, pushing up demands for equity. So assume that capital allocated to investment banking rises about 5 percent a year.

That leaves costs. Though compliance expenses are still rising, banks should be able to trim more fat elsewhere. Cutting operating expenses by 2 percent a year should be possible for most banks.

Steering clear of new legal entanglements may be beyond some firms. Volatile markets could also leave some nursing unexpected losses. It’s also true that most banks keep extra capital at the group level, which can flatter the true state of divisional ROEs. Even so, a bit of discipline could help investment banks pay their way again – and not before time.