U.S. student loans could one day need nearly a $500 billion bailout – perhaps the biggest government rescue yet. Borrowing for education has soared over the past decade, ballooning to $1.2 trillion and growing far faster than GDP. With the feds on the hook for much of the debt, it’s a mess in the making.

The growth in student debt has several causes. Employers increasingly prefer to hire people with post-secondary degrees, boosting enrollment. Meanwhile, education costs have increased twice as fast as inflation since the 1990s. With the government backing some 90 percent of college loans, there’s also the danger of lax underwriting.

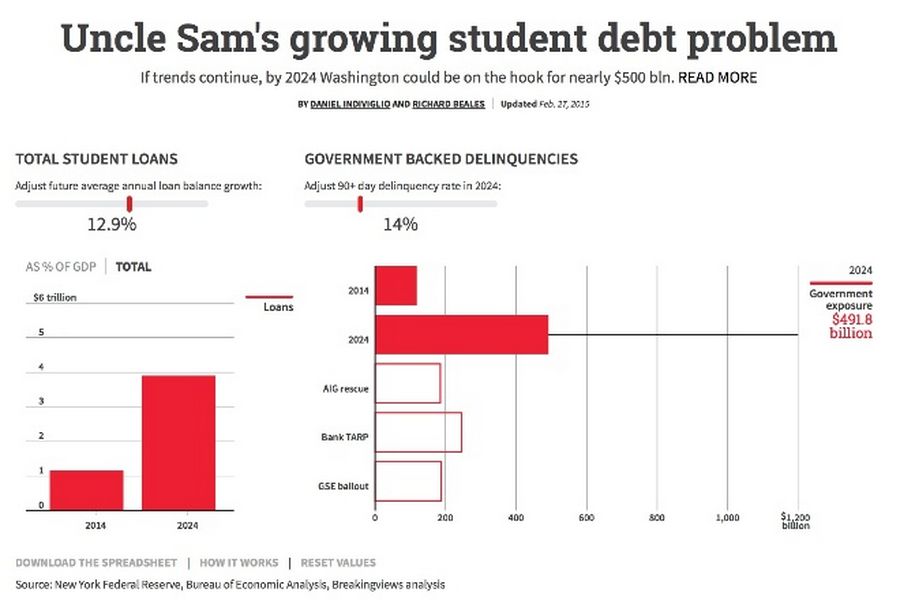

Over the past decade, student loan balances have averaged 13 percent annual growth and now roughly match credit card and home equity debt combined. A new Breakingviews calculator shows that if this pace persists, education debt would near $4 trillion by 2024. That’s over 14 percent of projected GDP, up from under 7 percent in 2014, using Federal Reserve estimates.

Default risk darkens the picture. While delinquencies in other asset classes have fallen in the post-crisis recovery, student debt payments at least 90 days past due have jumped over the past three years to top 11 percent of balances, up from 8.5 percent. Suppose that moves up to 14 percent in 2024, and the delinquent balance would exceed the half trillion dollar mark. That may even be conservative: 2009 vintage borrowers are already in much worse shape than that, according to the New York Fed.

The federal government guarantees 90 percent of today’s student loans. If that continues and Uncle Sam ends up covering all those 90-day delinquent loans in 2024, the total cost would be about double the $245 billion that banks got under the Troubled Asset Relief Program, never mind the sub-$200 billion rescues handed to mortgage guarantors Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and insurer American International Group.

The government eventually recouped those financial crisis-era capital infusions. Unsecured student loans might not fare so well, since it’s not obvious how individual borrowers would get back on track and debt collectors could find it politically pricklier to go after American university alumni than financial firms. Rather than banks that are too big to fail, the next decade’s big bailout could be of people too qualified to pay.