China’s strict capital controls are designed to shield the economy from flighty foreign money. In practice, they haven’t stopped a tremendous build up of fickle cash from abroad. There’s enough to create a serious nuisance if it starts to flow the other way.

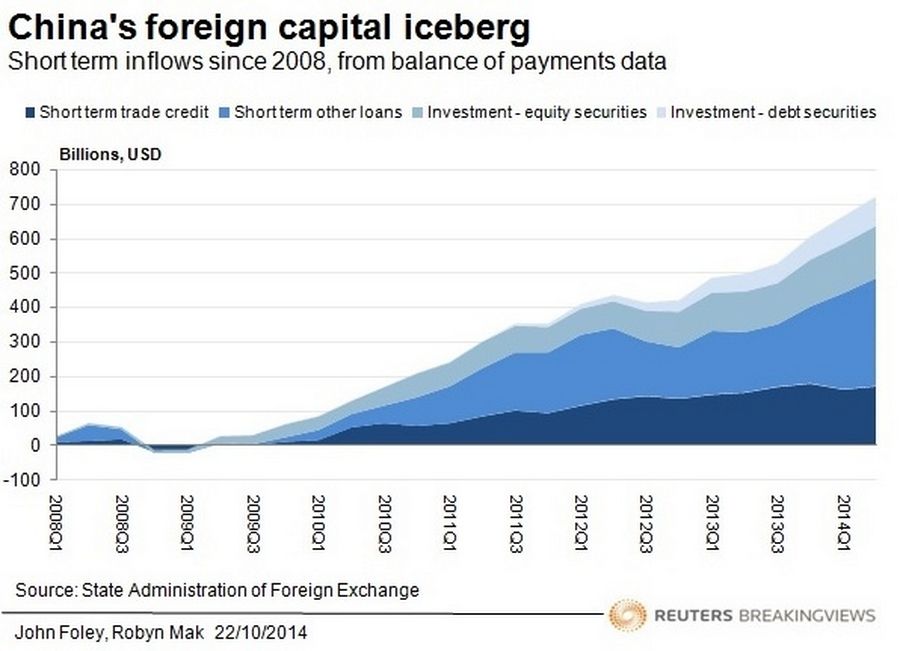

The People’s Bank of China allows money to cross the border for trade or long-term investment, but generally frowns on short-term speculation. Nevertheless, central bank data suggests $725 billion of what might be called “hot money” has piled up since 2008. That’s the combination of short-term funds Chinese residents have borrowed from foreign lenders, and securities they have sold to overseas investors, minus anything that was repaid or sold.

The real quantum of hot money is undoubtedly greater. Some activity that passes as trade is actually cover for transferring speculative capital. Anomalies like the 34 percent increase in exports to Hong Kong in September suggest widespread shenanigans.

Most of the inflows have come because rates in China are so much higher than in Western economies. Add in the yuan’s rise against the dollar over the years, and the returns for foreign investors have been too good to ignore.

The $725 billion pile is unlikely to trigger a balance of payments crisis – where a country is left without enough foreign currency to repay foreign debts or pay for crucial imports. Even if holders demanded their money back en masse, the central bank’s $3.9 trillion of foreign reserves can satisfy all of their claims. A bigger risk is that an outflow leaves banks short of deposits which fund domestic loans. Even if the central bank injected emergency funds, there’s no guarantee that spooked banks would want to lend.

The mood music is already troubling. China’s foreign reserves have fallen by $106 billion over the past three months, and local-currency deposits grew at 9.3 percent in September, their slowest rate on record. That suggests money is leaving China, although some will be due to tourism and relaxed rules on foreign investment.

The recent strengthening of the yuan suggests the People’s Bank of China wants to get speculative money flowing back in. It is also planning to inject money into banks directly. But it’s not ideal when monetary policy becomes hostage to short-term capital flows. China’s barriers have served it well, but its economy is more driven by what happens outside than planners might like to admit.