Economies binging on leverage are all alike – fast-growing and happy. But each country struggling to pay down debt is unhappy in its own way.

Right now it’s China’s turn to be glum. Credit to the non-financial corporate sector has swelled to an annual average of 150 percent of GDP, from less than 100 percent six years ago, according to data compiled by the Bank for International Settlements. And even this may not be an accurate count of the IOUs hiding in the country’s opaque shadow-banking system. More alarmingly, debt is accumulating just as the economy’s potential rate of growth is slowing because of population ageing.

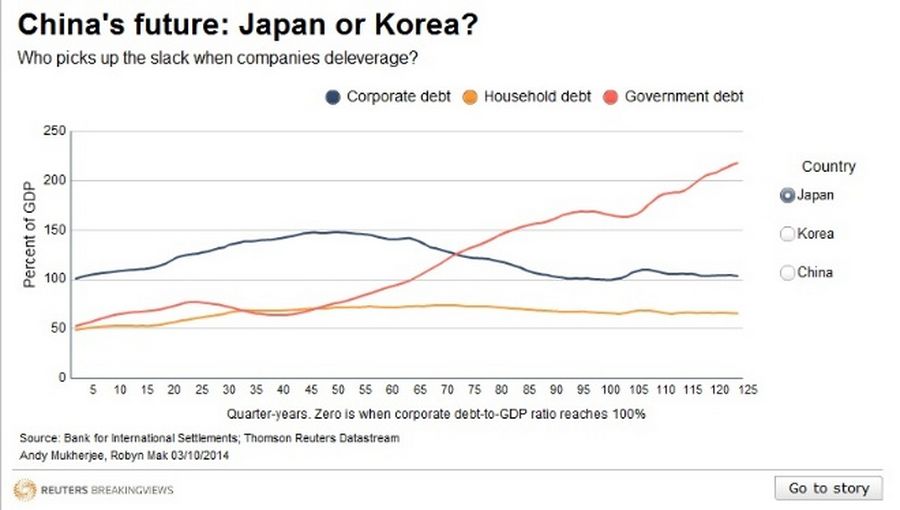

Japan and South Korea offer contrasting examples of how not to deal with this kind of problem. The two economies pursued very different strategies for reducing the level of debt owed by companies.

In Japan, companies had borrowings equivalent to 140 percent of GDP by the early 1990s – similar to the situation in today’s China. There too, the buildup in borrowings had been rapid. As its companies began to deleverage, Japan compensated for weak private credit demand by boosting public debt, which has ballooned to more than 200 percent of GDP.

Corporate debt did shrink. But in the process Japan fell into two decades of deflationary stagnation. The economy became comatose. With private borrowers on strike, the nation’s banks have come to own a third of the government’s debt. A spike in bond yields has the potential to cause massive valuation losses for the financial system.

Things turned out very differently for Korea. When the Tiger economy got whipsawed by the 1997 Asian crisis, its corporate debt stood at about 100 percent of GDP, having grown from 65 percent in the early 1990s. The deleveraging that followed was not as severe as it was in Japan. But the policy response to dealing with it was different. The Korean government didn’t become the borrower of last resort. Instead, it pushed consumers to load up on debt, which ended up causing a credit-card crisis in 2003.

The problem has worsened since then. Household debt is now 80 percent of GDP, up from 50 percent in 1998. Now Korean consumers are refusing to spend. Hence, companies don’t want to invest. The finance minister recently warned that the nation is entering “an early stage of deflation.”

How can China avoid ending up as another Japan or Korea? The People’s Republic has one big advantage. Interest rates on bank deposits are still under Beijing’s sway. Once they are freed up, fierce competition for funds could increase lenders’ costs, prompting them to chase riskier borrowers. That could push an already-stressed system over the edge. Korea had its financial crisis within one year of liberalizing deposit rates.

The mainland needs to do a few things differently. One is to prevent a Japanese-style collapse in property prices, if that’s possible. A “help-to-buy” programme for homebuyers in the most oversupplied real-estate markets – available only for projects already underway – could help developers clear their inventory and pay down debt. China’s relatively small fiscal deficits give it some firepower.

Rebalancing the economy would also help. A somewhat slower pace of GDP expansion is now inevitable, but producers’ debts, in real terms, are still rising. That’s because the prices they get for their output have been falling for 30 months. To prevent a future debt crisis, China needs to scrap output in industries with excess capacity, like steel. Policymakers also need to align production away from anaemic export markets and toward local consumption, where faster growth is possible.

China can no longer rely on an expanding, young population to help it grow. By 2025, the Chinese society will be as old as Japan’s in the early 1990s. That leaves productivity gains, like reforms of state-owned enterprises, as the best bet. In 1960, Japanese workers were only 30 percent as productive as their North American counterparts. By early 1980s, they were 70 percent as efficient. Once Japanese productivity began to wane, debts became a problem. Something similar happened in chaebol-dominated Korea, too.

Lulled by rapid growth, Japan and Korea left their corporate sectors unreformed for too long. By following in their footsteps, China would script its own tale of unhappiness.