“Charlie and I favor repurchases when… its stock is selling at a material discount to the company’s intrinsic business value.” It takes courage to contradict Warren Buffett on matters related to investing, but the Berkshire Hathaway boss is leading investors up the wrong path with share buybacks.

Over the last decade, buybacks made up 60 percent of quoted American corporations’ total cashflow to equity holders, according to Thomson Reuters Datastream. It is easy to see why companies go for them. They usually pump up growth of reported earnings per share, cut back on shareholders’ tax payments and are more flexible than dividends.

But the thinking behind all of those advantages is muddled. In reality, the price of a buyback doesn’t affect whether it is a good idea or not. Buybacks should be eliminated, not endorsed.

What happens in a buyback?

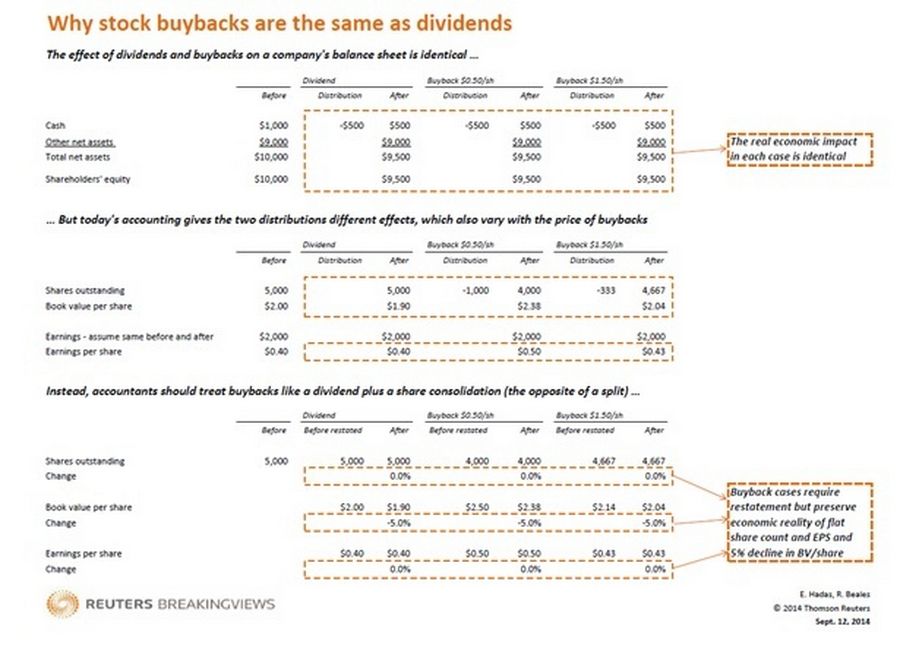

Think purely economically, and buybacks and dividends are the same. Both are a distribution of cash to equity holders.

The two look different, to be sure. But in both cases, shareholders receive money they already effectively own. The funds move from the company’s bank account to the shareholders’. But what investors have a claim on afterwards is identical: a quantity of cash, and everything else the company owns.

The cash from traditional dividends is paid evenly, per share, while cash from the buyback goes only to the shareholders who take part. That amounts to a redistribution of the ownership interest. Shareholders who sell to the company end up with a smaller percentage of the shares outstanding, while other holders end up with more. For all of them as a group, it is just as if they used the cash from a conventional dividend to buy more shares.

Accountants to the non-rescue

There’s another difference: after a dividend, the number of shares outstanding remains the same, but after a share buyback, it declines. So some performance measures that are expressed “per share,” like earnings, look different after each transaction. Accountants should – but don’t – adjust the numbers so economically identical transactions look the same in financial statements.

The technique for doing that is already familiar. When companies decide to change how many shares they have outstanding, splitting them or crunching them together, these shifts are neutralised in the accounts by adjusting historical share numbers. That way the earnings per share aren’t altered by a change that doesn’t affect what the company is, or does.

For buybacks, the rules are different. The cash distribution is treated as a return of capital. In other words, the accountants calculate as if the company were shrinking its business, in which case it makes sense to reduce the share count proportionately.

Such corporate redefinitions do happen. For example, the UK insurer and asset manager Standard Life announced on Sept. 4 it will use repurchases to give shareholders most of the proceeds from selling its Canadian operations, which accounted for about a quarter of the total company’s value. But most buybacks, even gigantic ones like Apple’s $90 billion programme, are payments from the ordinary profits of doing business.

How price matters

The wonky accounting creates the illusion that Buffett has helped perpetuate. If the share count were adjusted as for any other arbitrary share renumbering, the price of the purchase would have no effect on earnings-per-share growth. As it is, the opposite is true. The less the company pays for its shares, the more shares it can take out of circulation, and the more reported earnings per share go up.

Many people think buying back stock when the price is high is a bad sign. It can be – but only in the same way it would be questionable to pay a large straight dividend when the company’s valuation is rich. Why would a company with high growth expectations give shareholders cash that could be used for investments?

Buybacks at a high price are irritating to holders who are worried that the shares are expensive. If they don’t participate for some reason, they automatically end up with a higher proportion of the company. That doesn’t happen with dividends, which reduce everyone’s commitment by the same degree. The narrow viewpoint of an individual shareholder, sometimes not given the chance to participate in a buyback, is the only one from which repurchases differ from dividends and the price may matter.

Worse than irritating

Analysts and smart investors should be able to see past the confusions of buybacks, although most of them still need to open their eyes. But the problems aren’t limited to faulty accounting and involuntary portfolio adjustments.

Taxes are one issue. Buybacks attract far less tax than conventional dividends of the same value. That is fine for shareholders, but unfair to everyone else in society. Companies can’t be blamed for taking advantage, but it is odd that governments let this go unaddressed.

Buybacks are also opaque. Shareholders rarely know when the buyback is happening. That shouldn’t matter if shares are bought back at the market price, and in small enough chunks that the price is not disturbed. But sometimes that might not happen. The near-vacuum of information leaves room for market-savvy holders to sell high while less informed investors miss out.

Managers often use the opaqueness of buybacks to offset and keep attention away from their own share rewards. As long as the total share count does not change much from year to year, most analysts don’t focus on how many new shares executives have acquired, generally at far less than the market price.

What is to be done?

In sum, buybacks are complicated, confusing, misunderstood and unfair to governments and often to individual shareholders. In their defence, well, they have been around for a few decades.

Reforming buyback accounting to be consistent with other changes in the share count would be better than nothing. The resulting lack of EPS growth would sharply reduce the appeal of buybacks to managers, while the focus on buybacks as a form of dividend might attract critical attention from the tax authorities.

Still, finance is complicated enough; shareholders already need to be on guard when managers get clever. And dividends do everything a buyback should, only more clearly and fairly. There’s no reason something as fundamental as handing cash to shareholders should cause so much confusion. Buybacks should be banned altogether.