Skies above China’s big cities are turning blue, as its economic warning lights flash red. Across the country, PM2.5 readings – a measure of small particulates in the air – fell by 6 percent year on year in the first six months, Greenpeace reported in July. Beijing even scored the city’s least smoggy month since January 2011 according to data from the U.S. Department of State. Dirty industrials are leaving town and shutting down – but that’s just a quick fix.

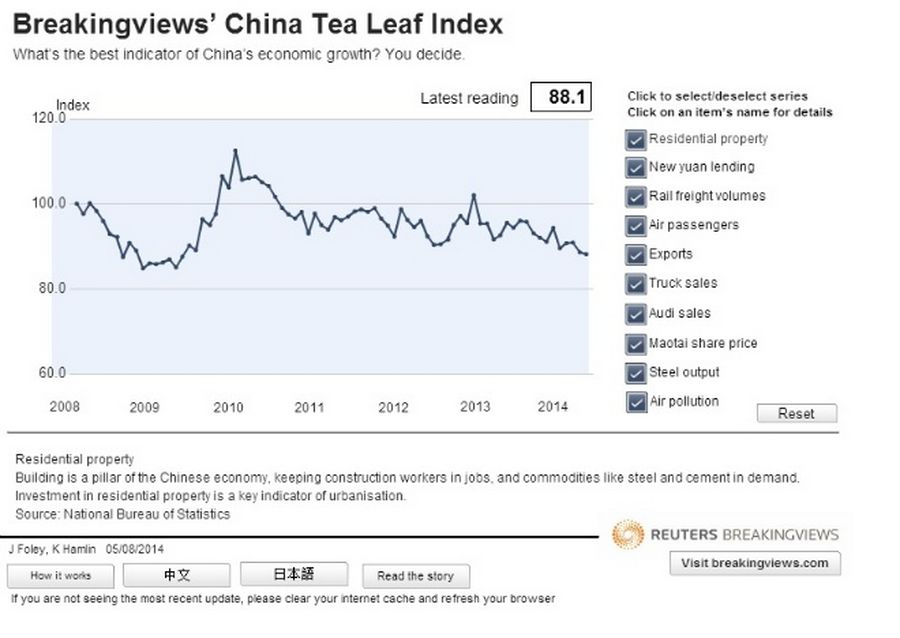

If grey skies are a sign of economic activity, the clear air suggests things are slowing fast. Breakingviews’ Tea Leaf Index, an alternative measure of China’s economic prospects, dropped to its lowest level since May 2009 in June. Signs are appearing that the industrial economy is in some trouble – for example, diesel demand is likely to fall for the first time in a decade in 2014, Reuters reported on Aug. 7.

But since clean air became a target, it has also become harder to interpret. Only nine of 161 Chinese cities achieved air quality monitoring standards in the first half of this year, according to the Ministry of Environmental Protection. Some problems have just been shunted from one area to another. While Beijing enjoyed a 10 percent year-on-year fall in PM2.5 levels in the first six months, Jiangsu suffered a 10.6 percent increase as steel production leapt 9 percent year on year, soaking up demand from places like Hebei where many plants closed.

In a country like China where the government’s hold over big businesses is strong, targeted top-down pressure is effective. The government can make dramatic gestures such as threatening disciplinary action against officials who miss environmental targets, or naming and shaming the worst offenders.

Further ahead, polluters must face robust institutions with hefty carrots and sticks. Despite new laws, it’s difficult to lodge a complaint or operate a pressure group without the government’s support. Enforcement is lacking, too. Beijing’s environmental bureau has been handling around 5,000-6,000 complaints a month, Reuters reported in March, a long to-do list for 500 or so environmental enforcers. Change is in the air, but more is needed to make a real difference.