Seller beware. That is an unusual warning, but it applies right now to the options market. Sellers of protection against large price moves have been pocketing gains. But many will suffer losses if markets become less calm.

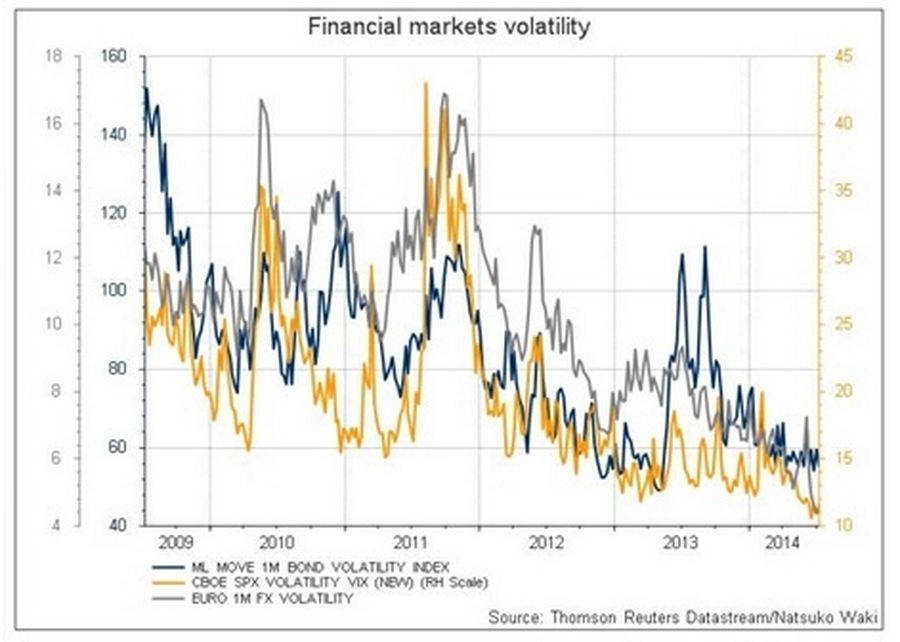

Market torpor has reached historic proportions. One measure is implied volatility, which encapsulates investors’ expectations of how much a particular market will move over a set period. The VIX index of expected U.S. equity volatility hit seven-year lows near 10 percent on July 3. The MOVE index of implied one-month volatility in Treasuries is at 55, near all-time lows just below 50.

The obvious reason for the declines in implied volatility is a sharp fall in actual volatility. Options traders basically expect the immediate future to look much like the recent past. But something else may also be responsible. Some investors are using the options market as a source of revenue.

Options are a sort of insurance. The revenue that options sellers receive for offering protection against large adverse market moves is a premium. That premium juices up the meagre yields available in today’s markets. As long as asset prices stay reasonably stable, the insurance policies don’t have to pay out anything.

Giant asset manager Pimco has said it has been selling such insurance to pick up yield, a practice known as selling volatility. It is unlikely to be alone, as the narrowing gap between implied and historical volatility in many major currencies suggests.

Implied volatility is typically higher than recent historic volatility, as sellers of volatility add a sort of uncertainty surcharge, a compensation for the risk of being wrong. The amount they can add depends on the balance of sellers and buyers. As the number of volatility sellers increases, the gap tends to narrow.

This has been happening in several major currency pairs. The difference between one-month implied and historical volatility is a half or less of mid-March levels in euro/dollar, dollar/yen, and sterling/dollar.

Investors may be tempted to accept a shrinking volatility risk premium out of a combination of desperation for higher returns and hope that market perma-calm will persist. But the lower the premium, the greater the losses if prices jolt. As they say in Latin, caveat venditor.