Japan’s pension reform debate is heating up. But it’s in danger of missing the wood for the trees.

University of Tokyo economist Takatoshi Ito, who headed a government-appointed panel into the management of Japan’s 200 trillion yen ($1.97 trillion) of public pension assets, has accused the giant Government Pension Investment Fund of “violating its fiduciary duty” by not slashing its allocation to domestic bonds. Ito’s broadside came after Takahiro Mitani, the GPIF’s president, suggested the government’s real objective was to pump more money into the stock market.

Both sides have a point. GPIF, which has assets of 124 trillion yen ($1.2 trillion), is at risk of losses if bond yields, which have been artificially suppressed by the Bank of Japan’s massive asset purchases, start to rise.

Yet Mitani’s concerns are more than just bureaucratic churlishness. In order to make payouts to pensioners the fund has to maintain a steady flow of income. A hasty shift into equities could backfire. Besides, a separate advisory committee wants GPIF to take minimal additional risks to chase a return target only marginally higher than the goal set five years ago.

It’s clear which side Japanese equity investors are rooting for. The benchmark TOPIX index, which responded enthusiastically to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s anti-deflation campaign in 2013, is down 7 percent in 2014. For bond buyers, though, the more important issue is the pension system’s ballooning liabilities.

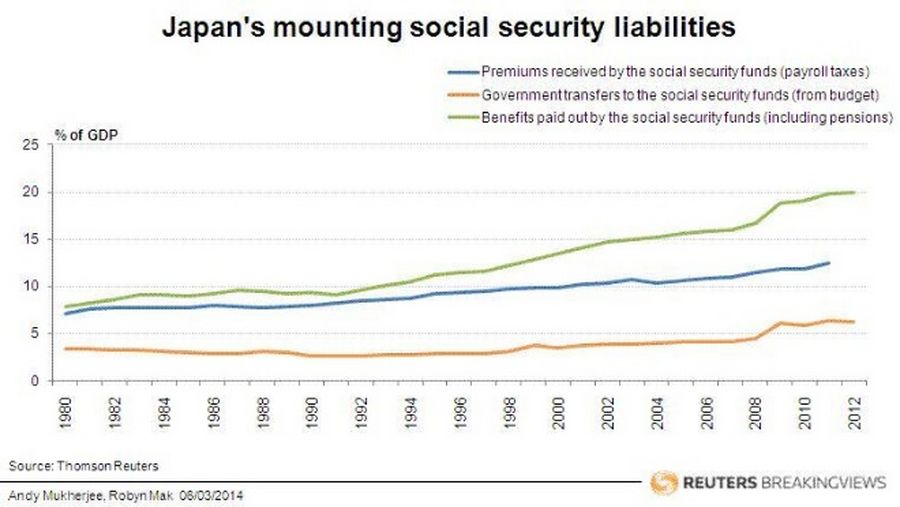

Past pension promises made to Japan’s private-sector workers are worth 830 trillion yen today, according to Hitotsubashi University scholar Noriyuki Takayama. That’s 170 percent of GDP. Pension assets from payroll taxes are just 40 percent of GDP. Add another 190 trillion yen of past budgetary support, and Japan’s total unfunded pension liabilities are still 100 percent of GDP.

Bridging this gap with future contributions from a shrinking workforce will be tough. Boosting the performance of pension funds helps a bit, but only makes a difference if superior returns are sustained over a very long period.

Any long-term solution requires politicians to prune pension benefits. Japanese bond investors worry that, rather than making tough decisions, the government will just borrow more instead. If investors lose faith in Japan’s creditworthiness, government bonds risk collapse. Squabbling over asset allocation in the face of such overwhelming danger is to miss not just the wood, but the entire forest.