China’s trust sector is the financial system’s enfant terrible. It’s a 10.9 trillion yuan ($1.8 trillion) industry built on taking short-term funding and channeling it into longer-term investments. That mismatch has already led some trust products to unravel, and more will follow. What causes concern isn’t so much trusts failing as them being foolishly rescued.

Trusts are essentially financial boxes. Anything can go inside, from loans to property or stocks and bonds. Trust companies build the box, fill it and slice the financial exposure into securities, known as trust products, which are sold to wealthy investors. The company takes a fee of around 0.7 percent, but in theory has no duty to compensate investors if what is in the box goes wrong.

Two recent trust products have put that to the test. One, called “Credit Equals Gold”, came close to default in January, only to be bailed out by an unnamed investor at the eleventh hour. Another, evocatively named “Songhua River #77 Shanxi Opulent Blessing Project”, has missed a $126 million payday, according to China Securities News.

Demand for trusts has grown prodigiously, because they typically pay more than double the 3.3 percent maximum one-year deposit rate that savers get from banks. Trust assets under management have increased by an average of 53 percent a year for the past three years. While the pace has slowed recently, the $1.8 trillion trusts had under management at the end of 2013 was still 8 percent more than the end of September.

Fault lines

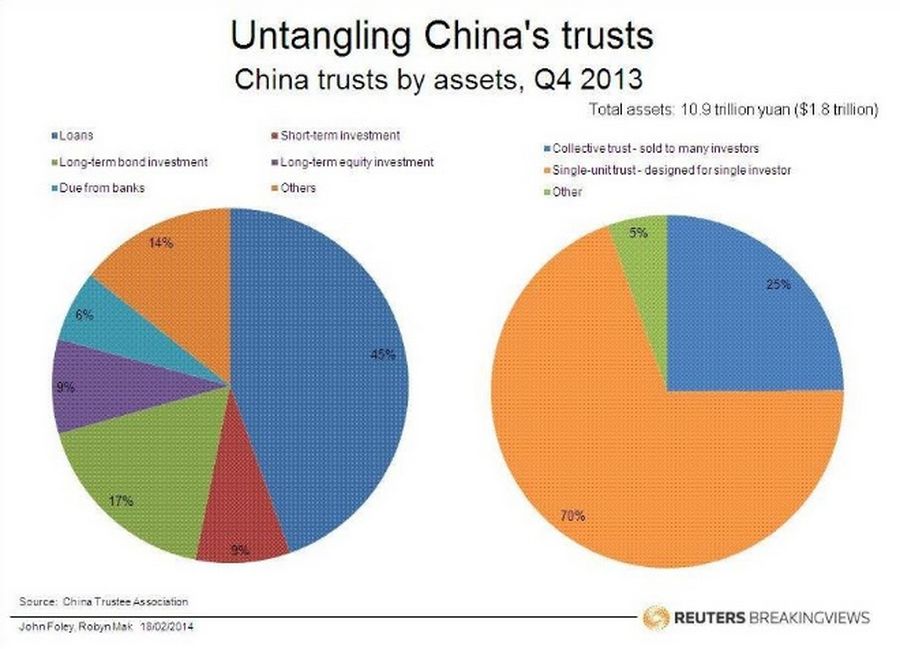

Not all trusts are equally worrisome. Only 45 percent of their assets are categorised as loans – although others may be loans disguised as equity. Meanwhile, just a quarter of assets belong to “collective” trusts, which are sold to multiple investors. This type, amounting to $450 billion, is the most vulnerable to messy public wrangling over who owes what to whom.

There are three reasons trusts inspire mistrust. The biggest is the potentially dangerous mismatch between short-term funds and longer-term investments. Many trust products last for two or three years. But for miners or infrastructure developers looking for financing, that can be the blink of an eye.

Second, trusts can be misused by banks eager to shuffle loans they’re not supposed to make off their balance sheets. So-called bank-trust co-operation has shrunk to 20 percent of total trust assets, but banks still sometimes advise on what goes in a product.

Finally, trust companies aren’t well understood. They’re regulated by the China Banking Regulatory Commission, which allows regulators to claim they don’t count as “shadow banking”. But capital buffers are thin. Even though they’re not on the hook, trust companies don’t want to see products fail: their business relies on selling more in future, often to the same investors.

The main risk is that companies which borrow from trusts can’t pay back. While many trusts have sound assets, the sector has also attracted overextended real estate developers, miners and local government projects desperate for cash. Shanxi Liansheng Energy, which borrowed from investors in Opulent Blessing, had tapped at least six different trust products, according to China Securities News.

When trusts go bust

Imagine a collective trust product defaults because the borrower can’t pay. The face-saving solution, and probably the most common, is for the bank, trust company or local government to find a white knight.

The danger is that such bailouts inspire false confidence among investors. Trust products aren’t for the masses – the minimum investment is 1 million yuan, around 30 times the average Beijing household’s disposable income. But even rich investors may still buy based on little more than their good relationship with the bank that sold the product.

More importantly, it might only take a few high-profile messes, where investors take a hit, before trust products from less well respected companies can’t find new buyers. A huge, well respected trust company like China Credit Trust may withstand the reputational hit of one default. A smaller rival like Jilin Trust, which birthed Opulent Blessing, may not.

If trust investors flee, borrowers dependent on their credit will sink. Bankruptcies, job losses and angry investors are the probable sequel. And other financial products that rely on the mistaken belief that investors are taking on no risk may also feel the chill.

Of course, in extremis China’s government could backstop the whole collective portion of the trust sector, which amounts to less than 5 percent of GDP. In that scenario, everyone would be spared short-term pain but also fail to learn any meaningful lessons about risk.

That kind of solution looks possible if defaults proliferate and investors lose faith, but China isn’t there yet. For now, buyers of trust products are protected by the sheer number of players, from trust companies and banks to borrowers, their suppliers, and local governments, which have good reasons to avoid a high-profile flop. Trust that such a situation cannot last.