The benefits of being labeled “too big to fail” may just outweigh the costs. Since regulators first published their list of global systemically important financial institutions, or G-SIFIs, the banks concerned have boosted capital and tamped down balance sheets. But smaller lenders, particularly in Europe, have done the same without joining the club. And shareholders seem not to notice much of a difference.

The theory behind the Financial Stability Board’s list is that banks which are too big, international or interconnected to fail should hold extra capital. This buffer offsets the benefit of support from taxpayers, and gives lenders an incentive to become simpler and smaller.

So far, however, there’s little sign of that happening. Though three banks have dropped off the G-SIFI list since it was first published two years ago, they were all under pressure from European authorities to shrink. Meanwhile, Standard Chartered, Spain’s BBVA and China’s ICBC have joined the club.

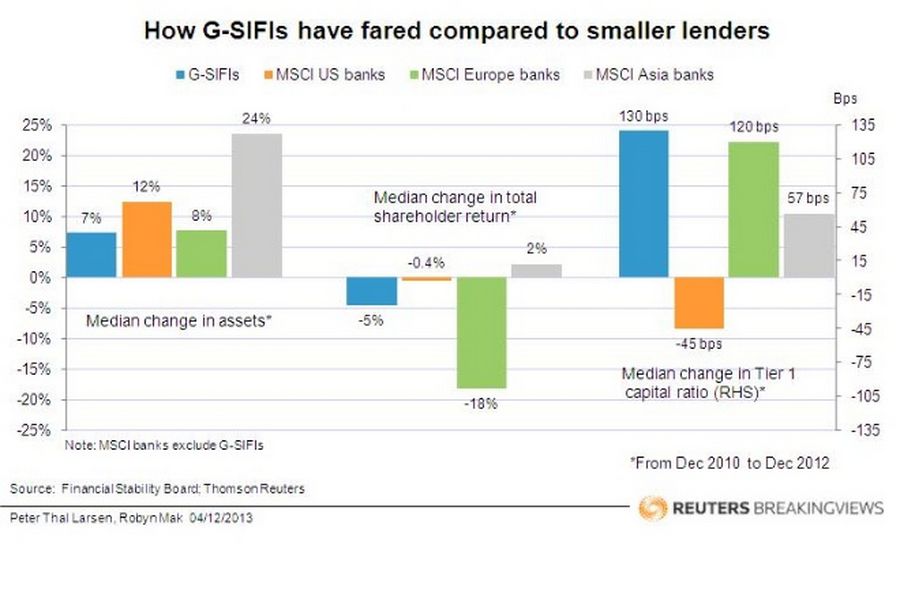

It’s true that the big banks are a bit safer and not much bigger: between 2010 and 2012, the median G-SIFI increased its Tier 1 capital ratio by 130 basis points and expanded total assets by just 7 percent, according to a Breakingviews analysis.

But smaller lenders have taken similar steps. Over the same two-year period, the median member of the MSCI European banks index – excluding those constituents that are also on the G-SIFI list - boosted Tier 1 capital by 120 basis points and total assets by 8 percent – roughly in line with its larger brethren.

Smaller lenders in other parts of the world fared relatively better. The median U.S. bank boosted assets by 12 percent and held 45 basis points less Tier 1 capital at the end of 2012 than two years earlier. Meanwhile, Asian banks expanded their balance sheets three times faster than G-SIFIs, and added half as much capital.

However, this failed to translate into a big advantage for shareholders. Over the two-year period, the median total shareholder return – capital appreciation plus dividends – was minus 5 percent for G-SIFIs. Asian and U.S. banks did only slightly better, while smaller European lenders limped in with minus 18 percent.

Any cross-border comparison of balance sheets and capital ratios is necessarily crude. And it does not capture other changes, such as shifts in funding costs as regulators push through plans to force creditors to bear the costs of bank failures. On the available evidence to date, however, the burden of being labeled a G-SIFI isn’t harsh enough to make it a club worth taking extraordinary efforts to avoid.