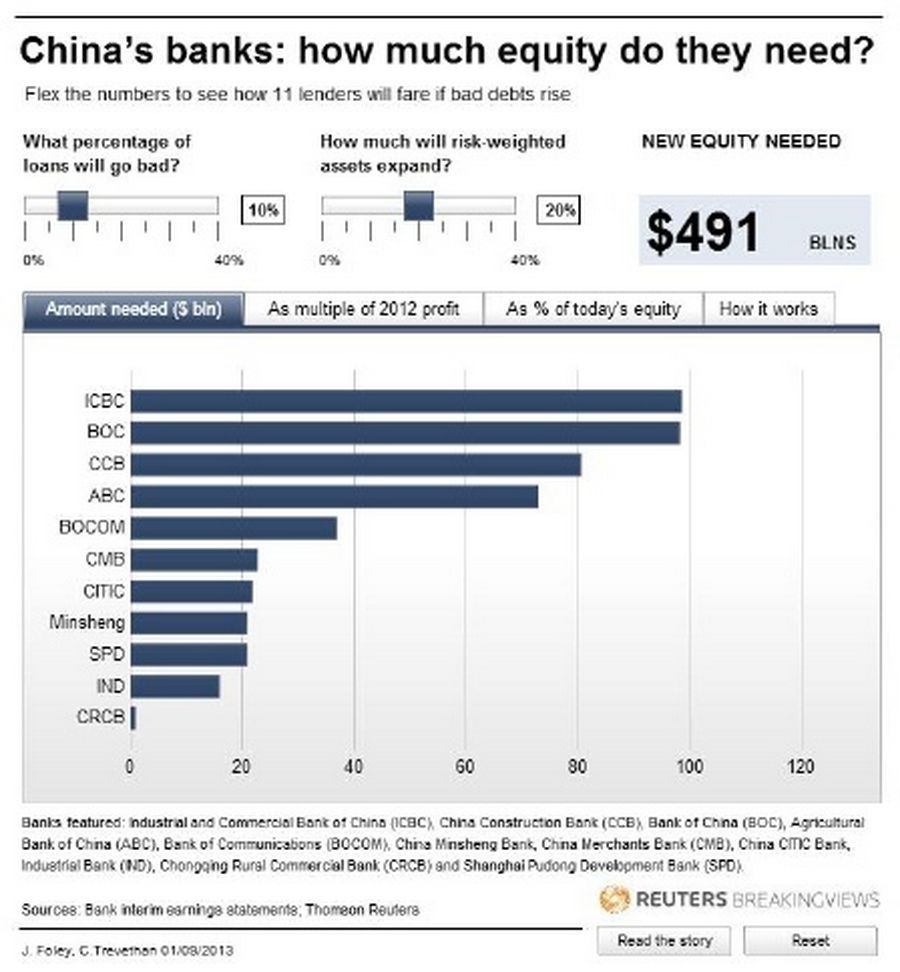

China’s bad debts could blow a $500 billion hole in bank balance sheets. That’s roughly how much extra equity the eleven biggest lenders might need if 10 percent of their loans went sour, according to a Breakingviews calculator. Though the chairman of ICBC, China’s biggest lender, thinks dismal bank valuations are “unfair”, the malaise is well deserved.

On the face of it, the industry is in great shape. Non-performing loans were below one percent of total loans at the end of June. But that number is meaningless. Many bad loans are simply rolled over while overdue loans, a herald of problems to come, are multiplying at some banks. Of particular concern is the $1.5 trillion of credit channelled to local governments through financing vehicles.

Assume the real bad loan ratio is a plausible ten percent, and that banks have to clean up their own mess. That would leave big lenders with $511 billion (3.2 trillion yuan) of bad debts they haven’t already set aside provisions for. Though capital ratios are currently above the minimum required by regulators, banks would need almost $350 billion of new equity to recover from the shock.

They also need capital to make new loans. If risk-weighted assets expand by 20 percent, the total equity required is $491 billion. In this scenario, ICBC would need to raise the equivalent of 53 percent of its current equity, Bank of China 73 percent. It could be more if regulators force lenders to take off-balance sheet loans back onto the books.

Fortunately, fees from selling wealth products and credit cards - not to mention cheap funding from capped deposit rates - mean earnings are healthy. Even $500 billion is just twice the eleven lenders’ combined pre-provision operating profit for 2012. They could also conserve capital by selling loans to China’s asset management companies, as Bank of Communications did recently, or cutting back the $50 billion they pay in annual dividends, most of which goes back to the government.

China may choose to defer the reckoning rather than face up to its bad debt problem. But valuations are already languishing: big banks trade at just 90 percent of their estimated book value a year from now, according to Bernstein Research. The hit, when it comes, will be large.