Japan’s prime minister should stop fretting about the country’s high corporate tax rate. Easing the burden on companies in an attempt to stimulate investment might seem appealing, but could prove both unnecessary and fiscally reckless. A temporary investment tax credit would be a better alternative.

According to media reports, Shinzo Abe is considering lowering Japan’s 38 percent corporate tax rate in order to encourage investment and offset the impact of the planned doubling in Japan’s consumption taxes by 2015.

However, deep and permanent cuts - the new rate could be between 25 percent and 30 percent, according to the Nikkei - could undermine bondholders’ perceptions of Japan’s fiscal stability. With more than half of government expenditure already financed by bond sales, the finance ministry will be loath to lose revenue from a levy which it expects will account for a fifth of total tax income this year. Any rise in long-term interest rates would also undo any benefit from the tax cut.

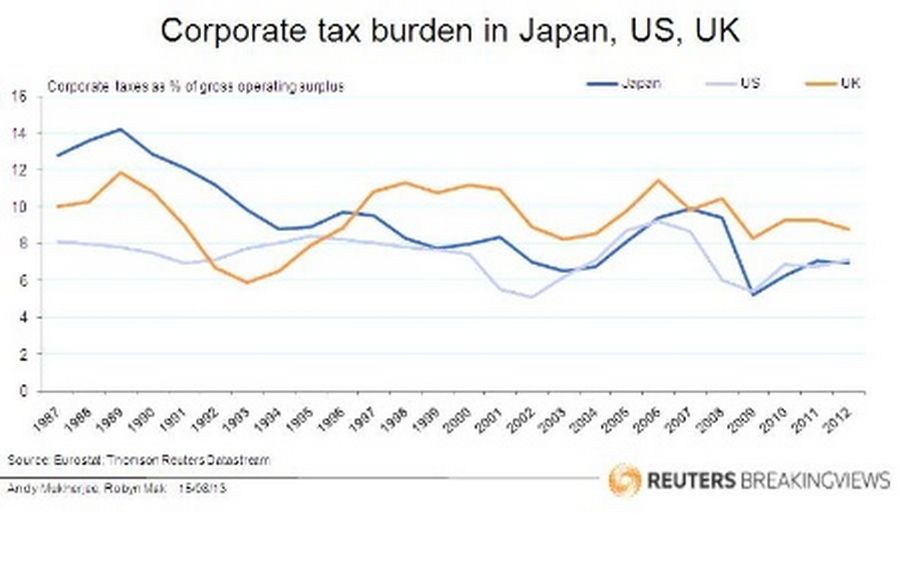

Besides, the intended beneficiaries won’t necessarily gain that much. Tokyo doesn’t confiscate corporate profit as harshly as the headline tax rate suggests, because many companies have built up tax losses to offset against earnings. Last year, Japanese companies handed 7 percent of their gross profit - what’s left after paying for workers and materials - to the taxman. That’s similar to the United States and less than Britain, which has a corporate tax rate of just 23 percent.

A better idea would be to offer short-term rebates on investment. A company that buys new machines this year could be allowed a deduction of an equal amount from its taxable income. That would stimulate spending, while ensuring the government would get its share of higher future profit.

Japan’s corporate tax rate is already scheduled to fall to 35.6 percent once an earthquake reconstruction surcharge expires in 2015. Experience of last year’s 2.6 percentage point cut suggests that, unless output surges, revenue will fall. With government debt in excess of 237 percent of GDP, it would be unwise to lose revenue that can’t be recouped in the near future.

Japan’s stock market will undoubtedly cheer lower corporate taxes, but the bond market won’t. It’s the latter that Abe must listen to.