Just as generals always fight the last war, investors tend to obsess over past crises. Six years after the peak of the credit bubble, some are convinced another one is being inflated. Use of the word “bubble” is on the rise. But this obsession may still be some way from popping.

It seems that hardly a day passes without a financial guru declaring a bubble in an asset class. In the past few months, investors and commentators have detected signs of irrational exuberance in government debt, prime real estate, junk bonds, gold, Japanese equities, and the virtual currency Bitcoin. The bullion selloff and Bitcoin collapse have emboldened the bubble-hunters to search for the next distorted market. Meanwhile, the debate rages about whether central bankers are to blame for it all.

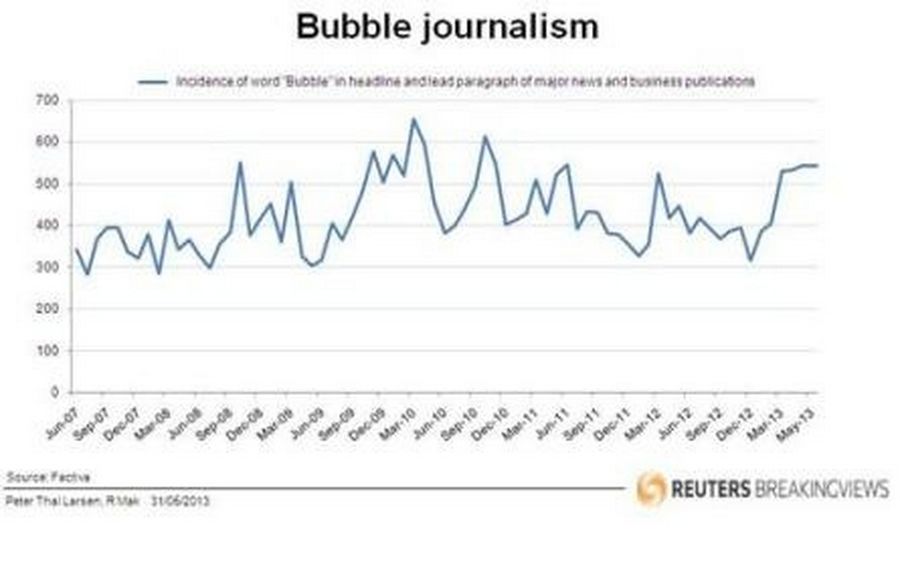

This onslaught of hot air points to the risk of a bubble in the use of the word bubble. In fact, mentions in the media are still some way short of their peak. Major news and business publications carried 544 articles with “bubble” in the headline or lead paragraph in May, according to Factiva. While that’s higher than in the recent past, it’s well below the high point of March 2010, when the bubble count hit 656.

Is increased talk of bubbles evidence of the real thing? Past experience suggests the opposite. In the summer of 2007 - when everyone involved in financial markets should have been shouting “bubble” at the tops of their voices - the number of articles with prominent mentions of the word ranged between 300 and 400 a month. The bubble count did not rise above 500 until October 2008, the month after Lehman Brothers collapsed.

Measuring bubble journalism is not remotely scientific. Results can be distorted by random articles about gas bubbles, or bubble wrap. What seems clear, however, is that the media is generally more enthusiastic about dissecting the aftermath of bubbles than about spotting new ones. As is the case with genuine financial bubbles, we may not be able to spot a bubble bubble until after it bursts.